Page 1 of 1

APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 5:06 am

by APOD Robot

A Jupiter Vista from Juno

Explanation:

A Jupiter Vista from Juno

Explanation: Why do colorful cloud bands encircle Jupiter?

Jupiter's top atmospheric layer is

divided into light zones and dark belts that go

all the way around the giant planet. It is high horizontal winds -- in excess of 300 kilometers per hour -- that cause the zones to spread out planet-wide. What causes these strong winds remains a

topic of research. Replenished by upwelling gas, zonal bands are thought to include relatively opaque clouds of

ammonia and water that block light from lower and darker atmospheric levels. One light-colored zone is shown in great detail in the

featured vista taken by the robotic

Juno spacecraft in 2017.

Jupiter's atmosphere is mostly clear and colorless

hydrogen and helium, gases that are not thought to contribute to the gold and brown colors. What compounds create these colors is another active topic of research -- but is hypothesized to involve small amounts of sunlight-altered

sulfur and

carbon. Many discoveries have been made from Juno's data, including that

water composes an unexpectedly high 0.25 percent of upper-level cloud molecules near Jupiter's equator, a finding important not only for understanding

Jovian currents but for the history of water in the entire

Solar System.

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 12:08 pm

by Michael J Joniec

What are the light colored dots all over the photo? Close inspection reveals many, many dots. Thanks! MJJ

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 1:32 pm

by orin stepanek

Sort of like a stick or stone would do in water; these clouds seem to split and go around something!

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 1:42 pm

by Chris Peterson

Michael J Joniec wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 12:08 pm

What are the light colored dots all over the photo? Close inspection reveals many, many dots. Thanks! MJJ

This image has been heavily contrast enhanced, which means any hot or warm pixels are going to be very apparent. There are naturally such pixels with this camera, and there are also pixels that are transiently hot because of being hit by cosmic rays or local radiation during the exposure (and the spacecraft is operating in a high radiation environment).

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:06 pm

by NCTom

Thanks, Orin, for pointing out that feature. I was curious about it as well. That would be one mighty big mountain top to reach that high! Maybe it is the wake from a Jovian submarine just below the surface. Being a little more serious, could a storm just below the surface cause the trailing streams?

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:10 pm

by E Fish

orin stepanek wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 1:32 pm

JupiterVista_JunoGill_1080.jpg

Sort of like a stick or stone would do in water; these clouds seem to split and go around something!

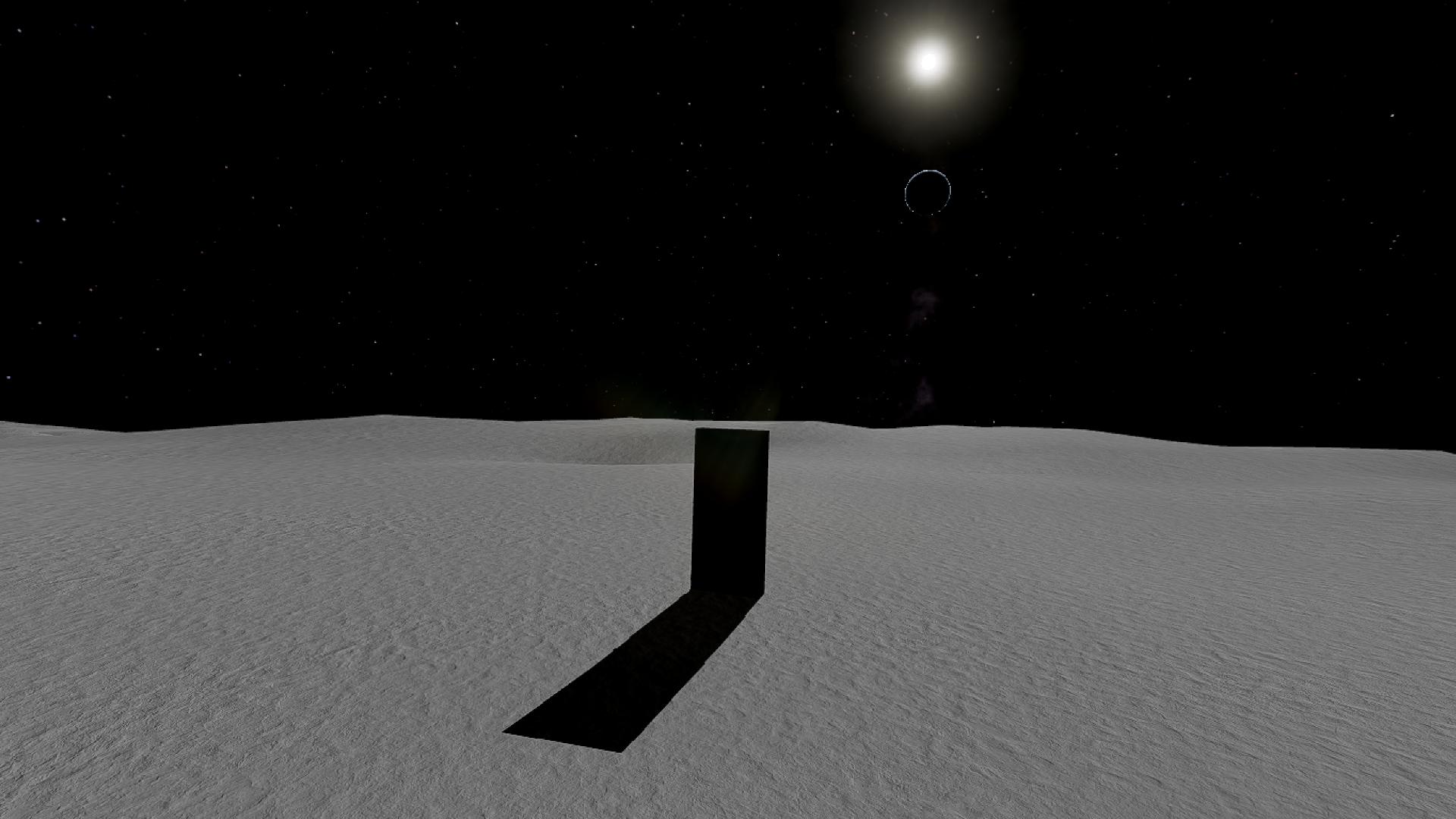

It's the monolith!!

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:26 pm

by Sa Ji Tario

Orin, it seems to me that it is because of the small whirlpool above and to the left

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:36 pm

by orin stepanek

NCTom wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:06 pm

Thanks, Orin, for pointing out that feature. I was curious about it as well. That would be one mighty big mountain top to reach that high! Maybe it is the wake from a Jovian submarine just below the surface. Being a little more serious, could a storm just below the surface cause the trailing streams?

I have no idea! Does anybody know what is under the clouds?

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:38 pm

by neufer

orin stepanek wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 1:32 pm

Sort of like a stick or stone would do in water; these clouds seem to split and go around something!

E Fish wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:10 pm

It's the monolith!!

It's a "thunderstorm."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter#Cloud_layers wrote:

<<[Jupiter's] cloud layer is only about 50 km deep, and consists of at least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region. There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer. Supporting the idea of water clouds are the flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter. These electrical discharges can be up to a thousand times as powerful as lightning on Earth. The water clouds are assumed to generate thunderstorms in the same way as terrestrial thunderstorms, driven by the heat rising from the interior.>>

Rubik's Cube has 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 "configurations."

Rubik's Cube has 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 "configurations."

If one had one standard-sized Rubik's Cube for each "configuration"

one could cover Jupiter's surface 2.25 times.

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 5:08 pm

by johnnydeep

orin stepanek wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:36 pm

NCTom wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:06 pm

Thanks, Orin, for pointing out that feature. I was curious about it as well. That would be one mighty big mountain top to reach that high! Maybe it is the wake from a Jovian submarine just below the surface. Being a little more serious, could a storm just below the surface cause the trailing streams?

I have no idea! Does anybody know what is under the clouds?

Mostly hydrogen and helium, getting denser the further down you go. There's likely no solid surface for 40000 miles or so, assuming a solid earth sized core, which may not even exist at all. As per usual, Wikipedia has more -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter#I ... _structure:

Jupiter was expected to either consist of a dense core, a surrounding layer of liquid metallic hydrogen (with some helium) extending outward to about 78% of the radius of the planet, and an outer atmosphere consisting predominantly of molecular hydrogen, or perhaps to have no core at all, consisting instead of denser and denser fluid (predominantly molecular and metallic hydrogen) all the way to the center, depending on whether the planet accreted first as a solid body or collapsed directly from the gaseous protoplanetary disk. However, the Juno mission, which arrived in July 2016, found that Jupiter has a very diffuse core, mixed into the mantle. A possible cause is an impact from a planet of about ten Earth masses a few million years after Jupiter's formation, which would have disrupted an originally solid Jovian core

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Mon Nov 23, 2020 11:23 pm

by orin stepanek

johnnydeep wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 5:08 pm

orin stepanek wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:36 pm

NCTom wrote: ↑Mon Nov 23, 2020 2:06 pm

Thanks, Orin, for pointing out that feature. I was curious about it as well. That would be one mighty big mountain top to reach that high! Maybe it is the wake from a Jovian submarine just below the surface. Being a little more serious, could a storm just below the surface cause the trailing streams?

I have no idea! Does anybody know what is under the clouds?

Mostly hydrogen and helium, getting denser the further down you go. There's likely no solid surface for 40000 miles or so, assuming a solid earth sized core, which may not even exist at all. As per usual, Wikipedia has more -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter#I ... _structure:

Jupiter was expected to either consist of a dense core, a surrounding layer of liquid metallic hydrogen (with some helium) extending outward to about 78% of the radius of the planet, and an outer atmosphere consisting predominantly of molecular hydrogen, or perhaps to have no core at all, consisting instead of denser and denser fluid (predominantly molecular and metallic hydrogen) all the way to the center, depending on whether the planet accreted first as a solid body or collapsed directly from the gaseous protoplanetary disk. However, the Juno mission, which arrived in July 2016, found that Jupiter has a very diffuse core, mixed into the mantle. A possible cause is an impact from a planet of about ten Earth masses a few million years after Jupiter's formation, which would have disrupted an originally solid Jovian core

A surmise at best; but probably pretty accurate; my Mom always said about the unknown, "only God knows"

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 12:00 am

by TheOtherBruce

Fascinating to see the small-scale structure of these clouds. Well, "small" in relative terms — the swirls that are barely big enough to see in the central white zone must be about the same size as similar weather patterns seen on Earth.

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 2:51 am

by mitcoyote

Question: Jupiter is considered a "gas giant," but its density is ~ 1.3 g/cm^3, or about 30% denser than liquid water. If it were a liquid giant, that's what its density would be, so...why is it a gas giant? I'm sure there's a good reason, but it beats me.

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 3:11 am

by neufer

mitcoyote wrote: ↑Tue Nov 24, 2020 2:51 am

Question: Jupiter is considered a "gas giant," but its density is ~ 1.3 g/cm

3, or about 30% denser than liquid water. If it were a liquid giant, that's what its density would be, so...why is it a

gas giant? I'm sure there's a good reason, but it beats me.

- Jupiter is warm enough to be mostly

gaseous (or "supercritical fluid"  )

)

even under high pressures/densities.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triple_point wrote:

<<The triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium. It is that temperature and pressure at which the sublimation curve, fusion curve and the vaporisation curve meet. For example, the triple point of mercury occurs at a temperature of −38.83440 °C and a pressure of 0.2 mPa.

A critical point (or critical state) is the end point of a phase equilibrium curve. The most prominent example is the liquid–vapor critical point, the end point of the pressure–temperature curve that designates conditions under which a liquid and its vapor can coexist.

At higher temperatures, the gas cannot be liquefied by pressure alone. At the critical point, defined by a critical temperature Tc and a critical pressure pc, phase boundaries vanish.>>

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 3:28 am

by mitcoyote

Thanks. I still don't quite get it.

The higher the pressure, the more likely a material is to be liquid than gas. Likewise, the lower the temperature, the more likely liquid than gas. Compared to Earth, Jupiter is both colder (a lot colder) and the pressure is far higher, so it seems it ought to be liquid rather than gaseous. I get that it might be a supercritical fluid, but why is it assumed that it isn't just garden variety liquid water/ammonia/methane?

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 3:35 am

by neufer

mitcoyote wrote: ↑Tue Nov 24, 2020 3:28 am

Thanks. I still don't quite get it.

The higher the pressure, the more likely a material is to be liquid than gas. Likewise, the lower the temperature, the more likely liquid than gas. Compared to Earth, Jupiter is both colder (a lot colder) and the pressure is far higher, so it seems it ought to be liquid rather than gaseous. I get that it

might be a supercritical fluid, but why is it assumed that it isn't just garden variety liquid water/ammonia/methane?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gas_giant wrote:

<<

A gas giant is a giant planet composed mainly of hydrogen and helium. Gas giants are sometimes known as failed stars because they contain the same basic elements as a star. Jupiter and Saturn are the gas giants of the Solar System. The term "gas giant" was originally synonymous with "giant planet", but in the 1990s it became known that Uranus and Neptune are really a distinct class of giant planet, being composed mainly of heavier volatile substances (which are referred to as "ices"). For this reason, Uranus and Neptune are now often classified in the separate category of ice giants.

Jupiter and Saturn consist mostly of hydrogen and helium, with heavier elements making up between 3 and 13 percent of the mass. They are thought to consist of an outer layer of molecular hydrogen surrounding a layer of liquid metallic hydrogen, with probably a molten rocky core. The outermost portion of their hydrogen atmosphere is characterized by many layers of visible clouds that are mostly composed of water and ammonia. The layer of metallic hydrogen makes up the bulk of each planet, and is referred to as "metallic" because the very large pressure turns hydrogen into an electrical conductor. The gas giants' cores are thought to consist of heavier elements at such high temperatures (20,000 K) and pressures that their properties are poorly understood.>>

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 3:46 am

by mitcoyote

What kind of density does metallic hydrogen have? I've looked but can't seem to find either a measured or calculated value. Seems it would have to be denser than liquid water.

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Tue Nov 24, 2020 2:04 pm

by neufer

mitcoyote wrote: ↑Tue Nov 24, 2020 3:46 am

What kind of density does metallic hydrogen have? I've looked but can't seem to find either a measured or calculated value. Seems it would have to be denser than liquid water.

- No heavy oxygen nuclei however : ~0.6 g/cm3 at "low" pressure.

(When I was in graduate astronomy at Univ. of Md. (c1970) a fellow

student recommended doing any optional essay on planetary interiors

because one can basically claim anything one wanted.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallic_hydrogen wrote:

<<In March 1996, a group of scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory reported that they had serendipitously produced the first identifiably metallic hydrogen for about a microsecond at temperatures of thousands of kelvins, pressures of over 100 GPa and

densities of approximately 0.6 g/cm3

A diagram of Jupiter showing a rocky core overlaid by a deep layer of liquid metallic hydrogen and an outer layer predominantly of molecular hydrogen. Jupiter's true interior composition is uncertain. For instance, the core may have shrunk as convection currents of hot liquid metallic hydrogen mixed with the molten core and carried its contents to higher levels in the planetary interior. Furthermore, there is no clear physical boundary between the hydrogen layers—with increasing depth the gas increases smoothly in temperature and density, ultimately becoming liquid.>>

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Wed Nov 25, 2020 7:09 pm

by TheOtherBruce

Some interesting info there about metallic hydrogen. But Jupiter has quite a lot of helium as well; up to 1/4 by mass in the interior, according to Wikipedia. Is there any info on how this would affect the metallic hydrogen — does it mix, or would it be forced out in the deeper, denser layers? I can't find anything in the articles I've been browsing.

Re: APOD: A Jupiter Vista from Juno (2020 Nov 23)

Posted: Wed Nov 25, 2020 10:17 pm

by neufer

TheOtherBruce wrote: ↑Wed Nov 25, 2020 7:09 pm

Some interesting info there about metallic hydrogen. But Jupiter has quite a lot of helium as well; up to 1/4 by mass in the interior, according to Wikipedia. Is there any info on how this would affect the metallic hydrogen — does it mix, or would it be forced out in the deeper, denser layers? I can't find anything in the articles I've been browsing.

- Compressible solid helium certainly might help to get the average density up over one.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helium wrote:

<<[Helium] is present at about 24% of the total elemental mass, which is more than 12 times the mass of all the heavier elements combined... Solid helium requires a temperature of 1–1.5 K at about 25 bar of pressure.

The solid has a sharp melting point and has a crystalline structure, but it is highly compressible; applying pressure in a laboratory can decrease its volume by more than 30%. With a bulk modulus of about 27 MPa it is ~100 times more compressible than water. Solid helium has a density of 0.214 g/cm3 at 1.15 K and 66 atm; the projected density at 0 K and 25 bar is 0.187 g/cm3. At higher temperatures, helium will solidify with sufficient pressure. At room temperature, this requires about 114,000 atm.>>

However, note that:

- Average density Sun: 1.408 g/cm3

Average density Brown dwarf core: 10 to 1000 g/cm3

Average density Jupiter: 1.326 g/cm3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_dwarf wrote:

<<If the mass of the protostar is less than about 0.08 M

☉, normal hydrogen thermonuclear fusion reactions will not ignite in the core. Gravitational contraction does not heat the small protostar very effectively, and before the temperature in the core can increase enough to trigger fusion, the density reaches the point where electrons become closely packed enough to create quantum electron degeneracy pressure. According to the brown dwarf interior models, typical conditions in the core for density, temperature and pressure are expected to be the following:

This means that the protostar is not massive enough and not dense enough to ever reach the conditions needed to sustain hydrogen fusion. The infalling matter is prevented, by electron degeneracy pressure, from reaching the densities and pressures needed.>>

A Jupiter Vista from Juno

A Jupiter Vista from Juno