HiRISE Updates (2016 Sep 21)

Posted: Mon Oct 03, 2016 2:50 pm

Anna Urso wrote:River of Sand (ESP_045081_1875) (HiClip)

A dominant driver of surface processes on Mars today is aeolian (wind) activity. In many cases, sediment from this activity is trapped in low-lying areas, such as craters. Aeolian features in the form of dunes and ripples can occur in many places on Mars depending upon regional wind regimes.

The Cerberus Fossae are a series of discontinuous fissures along dusty plains in the southeastern region of Elysium Planitia. This rift zone is thought to be the result of combined volcano-tectonic processes. Dark sediment has accumulated in areas along the floor of these fissures as well as inactive ripple-like aeolian bedforms known as “transverse aeolian ridges” (TAR).

Viewed through HiRISE infrared color, the basaltic sand lining the fissures’ floor stands out as deep blue against the light-toned dust covering the region. This, along with the linearity of the fissures and the wave-like appearance of the TAR, give the viewer an impression of a river cutting through the Martian plains. However, this river of sand does not appear to be flowing. Analyses of annual monitoring images of this region have not detected aeolian activity in the form of ripple migration thus far.

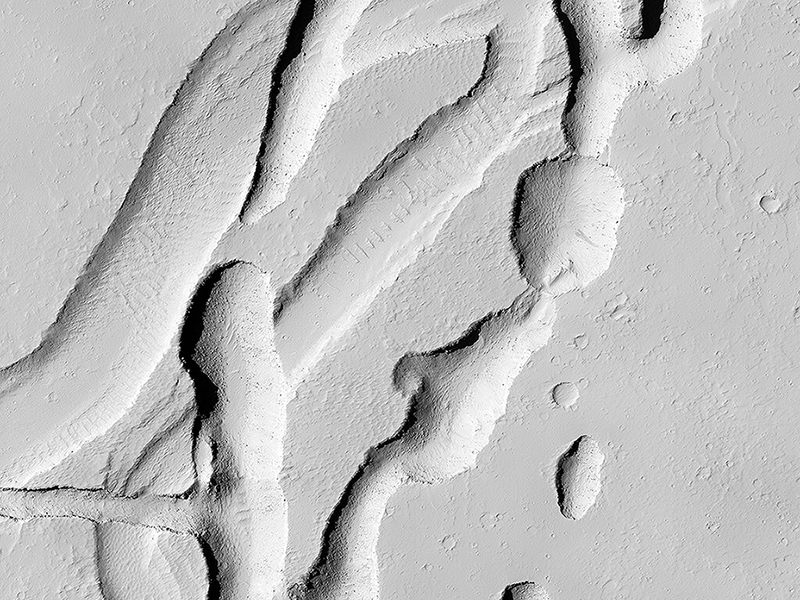

Sarah Sutton wrote:Intersecting Channels near Olympica Fossae (ESP_045091_2045) (HiClip)

This complicated area contains various types of channels, pits and fractures. We can determine the relative ages of the pits and channels based on which features cross-cut others. Older channels appear smooth-edged and shallow. Younger channels and pits are deeper and more sharp-edged, as well as less sinuous than the shallower channels.

What caused this array of various channels and intersecting pits?

This region is covered in vast lava flows. The collapse pits here may be collapsed lava tubes or where overlying rock “drained” into voids created by extensional faulting. The older smoother channel that seems to source from this region may have carried an outflow of groundwater. It continues on for over 100 kilometers (62 miles) (see ESP_045368_2040).

The orientation and shapes of these features make an interesting geological puzzle!

This is a stereo pair with ESP_044326_2045.

Henrik Hargitai and Ginny Gulick wrote:The Wind-Scoured Lava Flows of Pavonis Mons (ESP_045777_1765) (HiClip)

This image shows a circular impact crater and an oval volcanic caldera on the southern flank of a large volcano on Mars called Pavonis Mons.

The caldera is also the source of numerous finger-like lava flows and at least one sinuous lava channel. Both the caldera and the crater are degraded by aeolian (wind) erosion. The strong prevailing winds have apparently carved deep grooves into the terrain.

When looking at the scene for the first time, the image seems motion blurred. However, upon a closer look, the smaller, young craters are pristine, so the image must be sharp and the “blurriness” is due to the processes acting on the terrain. This suggests that the deflation-produced grooves, along with the crater and the caldera, are old features and deflation is not very active today. Alternatively, perhaps these craters are simply too young to show signs of degradation.

This deeply wind-scoured terrain type is unique to Mars. Wind-carved stream-lined landforms on Earth are called “yardangs,” but they don’t form extensive terrains like this one. The basaltic lavas on the flanks of this volcano have been exposed to wind for such a long time that there are no parallels on Earth. Terrestrial landscapes and terrestrial wind patterns change much more rapidly than on Mars.

M. Ramy El-Maarry wrote:What Lies Beneath: Surface Patterns of Glacier-Like Landforms (ESP_046039_2295) (HiClip)

The rotational axis of Mars is currently tilted by about 25 degrees, very similar to that of the Earth (at 23.4 degrees). However, while Earth’s axial tilt (also known as “obliquity”) tends to change very slightly over time (almost 3 degrees in 40,000 year-cycles), the obliquity of Mars is much more chaotic and varies widely from 0 to almost 60 degrees! The fact that it is currently similar to that of the Earth is merely a coincidence.

Currently, water-ice is stable on the Martian surface only in the polar regions. However, during times of “high obliquity,” that stability shifts towards the equatorial regions. We see evidence for recent periods of high obliquity on Mars in the form of features common in the mid-latitude regions, which planetary scientists call “viscous flow features,” “lobate debris aprons,” or “lineated valley fills.” These are all scientifically conservative ways of describing features on Mars that resemble mountain glaciers on Earth.

We now know from radar observations, particularly using the SHARAD instrument on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, that these features are really composed of mixtures of pure ice and dust, and as a result, many scientists have started using the term “glacier-like forms” (GLF) to describe some of them. The main reason that these feature are still present for us to observe nowadays—despite the inhospitable conditions for water ice in these latitudes—is that these “glaciers” are covered by thin layers of dust, which protect them from the atmosphere of Mars and prevents, or significantly slows down, the loss of ice through sublimation to the atmosphere.

However, if we were to take a look at this image of a “lobate debris apron,” we will see that some areas show numerous depressions, which suggests that these areas have lost some of the ice creating these “deflation features.” In addition, if we zoom in on one of these depressions, we will see surface polygonal patterns, which are common in cold regions on Earth (such as Alaska, northern Canada, and Siberia) and are indicators of shallow sub-surface water-ice.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

<< Previous HiRISE Update