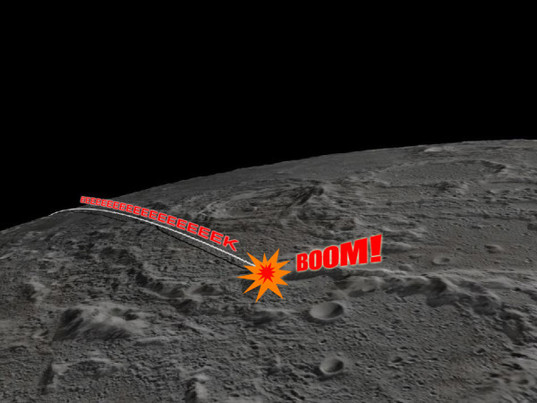

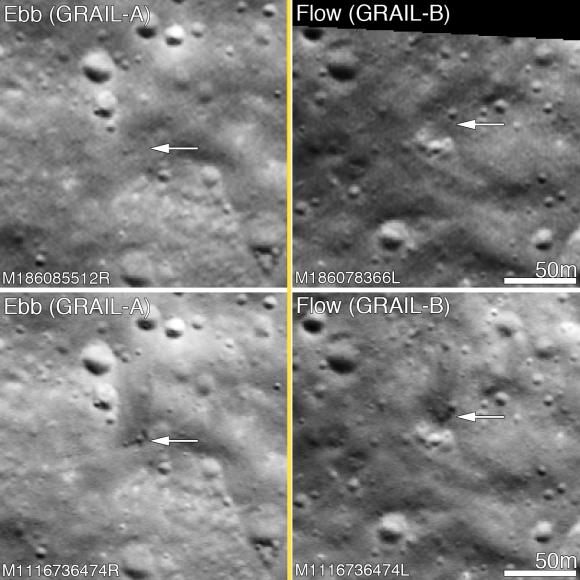

On December 17, 2012, the GRAIL mission came to an end, and the two washing machine-sized spacecraft performed a flying finale with a planned formation-flying double impact into the southern face of 2.5-kilometer- (1.5-mile-) tall mountain on a crater rim near the Moon’s north pole. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has now imaged the impact sites, which show evidence of the crashes.

But surprisingly, these impacts were not what was expected, says the LRO and GRAIL teams. The ejecta around both craters is dark. Usually, ejecta from craters is lighter in color – with a higher reflectance – than the regolith on surface.

“I expected the ejecta to be bright,” said LROC PI Mark Robinson at a press conference from the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference today, “because everybody knows impact rays on the Moon are bright. We are speculating it could be from hydrocarbons from the spacecraft.”

Typically ejecta from craters is brighter, since subsurface regolith tends to have a higher reflectance. The lunar regolith on the surface tends to be darker because of its exposure to the vacuum of space, and its exposure to cosmic radiation, solar wind bombardment, and micrometeorite impacts. Slowly over time, these processes tend to darken the surface soil.

Robinsons said they hydrocarbons could have come from fuel left in the fuel lines (JPL estimated a quarter to half a kilogram of fuel may have remained in the spacecraft – so not very much) or from the , spacecraft itself, which is made out of carbon material.

Additionally, the impact craters’ shapes were not as expected. The impacts formed craters about 5 m (15 ft) in diameter, and there is little ejecta to the south – the direction from which the spacecraft were traveling. “The spacecraft came in at a 1 or 2 degree impact angle,” said Robinson, “so this not a normal impact, as all the ejecta went upstream in the direction of travel.”

“I was expecting to see skid marks, myself,” said GRAIL principal investigator Maria Zuber. She added that she was committed to using every bit of fuel to mapping the gravity field at as low an altitude as possible. “I was determined that we would not end the mission with unused fuel because that would have meant we could mapped it even lower.

The spacecraft did end up being able to map the Moon from 2 km above the surface, the lowest altitude from which any planetary surface has ever been mapped, creating an extremely high resolution map.

Robinson said he was skeptical that they could find the impact craters, since the team has yet to find the impact sites of the Apollo ascent stages, which should be much bigger than the GRAIL impacts.

“Finding the impact crater was like finding a needle in haystack,” Robinson said, “as the images are looking at an area that is about 8 km wide and 30 to 40 km tall, and we were looking for something that is a couple of pixels wide.”

Robinson said he spent hours looking for it with no luck, only to see it later when he was on a conference call and was just looking at it out of the corner of his eye.

“It was really fun to find the craters,” he said.

While LRO’s camera was not able to image the actual impact since it occurred on the night-side of the Moon, the LAMP instrument (Lyman Alpha Mapping Project) on LRO was able to detect the plume of the impacts.

Kurt Rerhorford, PI of LAMP said the UV spectrograph was pointed towards the limb of the Moon to observe the gases coming out of the plumes. They did detect the two impact plumes which clearly showed an excess of emissions from hydrogen atoms. “We were excited to see this detection of atomic hydrogen coming from the impact sites,”Retherford said. “This is our first detection of native hydrogen atoms from the lunar environment.”

Retherford said further studies from this will help in determining the processes of how the implantation of solar wind protons on the lunar surface could create the water and hydroxyl that has been recently detected on the lunar surface by other spacecraft.