Slings and arrows of time

Posted: Tue Nov 15, 2011 2:38 pm

http://readingeagle.com/article.aspx?id=345693 wrote:

Many scholars write off controversial Shakespeare film

The Associated Press 11/14/2011

NEW YORK - <<O, for a juicy literary dispute that would pit scholars against Hollywood, with charges of snobbery, materialism, elitism and opportunism flying around like so many slings and arrows - not to mention the specter of young minds poisoned by the character assassination of a hero.

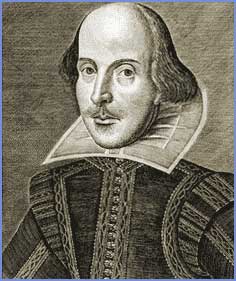

Heard about the new movie "Anonymous"? The film by Roland Emmerich, a director better known for apocalyptic blockbusters than period dramas, opened Friday. But already, its contention that Shakespeare was a simpleton, a fraud and perhaps a murderer who never wrote a word of those great plays has set off some epic sniping of which the Bard himself might be proud. "A new low for Hollywood," said Columbia University professor James Shapiro. "Completely grotesque," said Stanley Wells, of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Britain. Emmerich said he's been called names, and screenwriter John Orloff said one critic even suggested he be taken "to the tower" - the Tower of London, that is. Orloff dismisses Shapiro's complaints as "frothing at the mouth."

Not that the authorship dispute is new, of course. It has been around since at least the mid-19th century (even that time is in dispute). Nor is the film's main contention new, that the actual author was the Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere: There's a whole "Oxfordian" school of thought, along with a "Baconian" school (Francis Bacon). Some think it was playwright Christopher Marlowe, or even Queen Elizabeth I herself. But Emmerich's film goes further, pitting the story of Shakespeare in a political context involving a fight for succession using the plays as propaganda. As for Elizabeth: the Virgin Queen? Not so much. (The film suggests she had several children secretly, and one of them was born of incest.)

Also, some scholars are disturbed by the film's dismissal of complaints of factual errors with an "it's only a movie" explanation. "It's the best of both worlds for Emmerich," wrote Stephen Marche, a former Shakespeare professor, in The New York Times magazine. "He gets to question hundreds of years of legitimate scholarship ... because, after all, it's just a movie."

And then there's the educational push into schools. Sony, in concert with an educational company, has prepared study guides for educators on the authorship question, as with some previous films. "I don't have a problem with Roland Emmerich drinking the Kool-Aid," said Columbia's Shapiro. "But when he serves it to kids in paper cups, I do." The acrimony is mystifying to some of the actors.

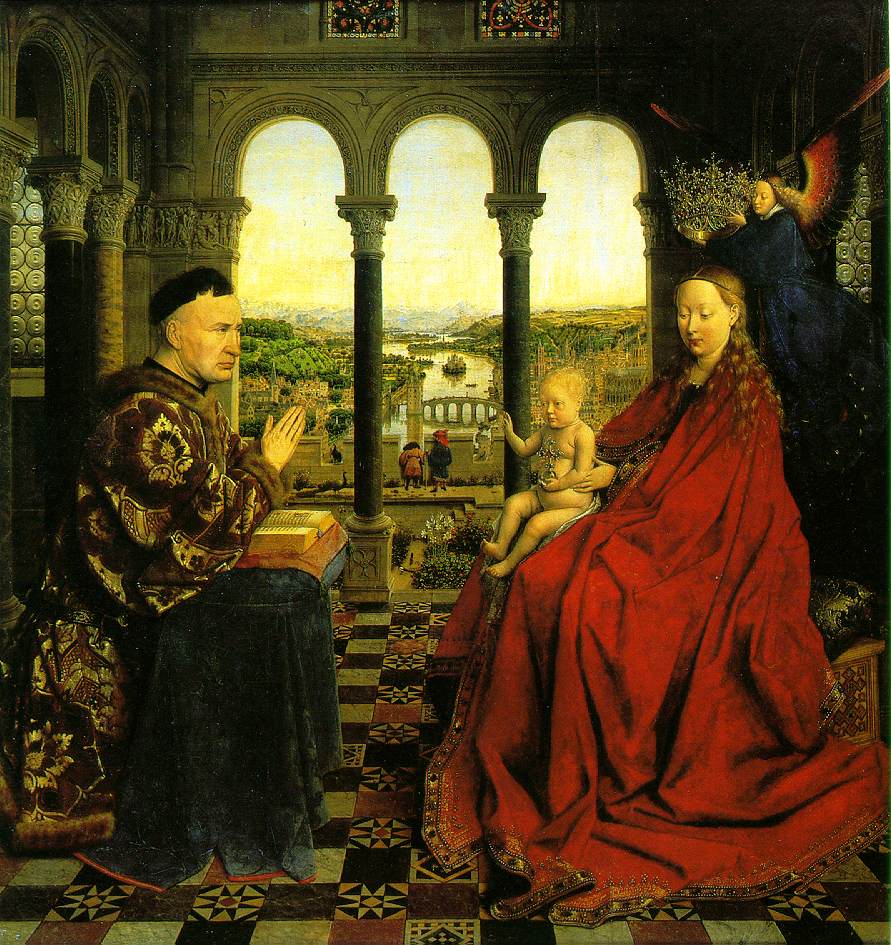

Rhys Ifans plays de Vere, and he feels like the authorship debate isn't even the central point of the film. "It's a political thriller," Ifans said. "It's a historical piece, a visual banquet. And it shows the potency of the theater as a vital form of change." Ifans enjoyed shooting the scenes where, as de Vere, he sits in a recreated Globe theater and mouths his own words as the crowd becomes entranced. He is, of course, the author, but must keep that secret. "I was really moved by the words," Ifans said. "We owe it to whoever wrote these plays - him, her or a group of people - to ask these questions."

The actor mimes pulling a text down from a shelf, and blowing off the dust.

"That's what Roland is doing," he said with a smile. "He's cleansing the plays, elevating them. It's really refreshing."

Joely Richardson plays the younger Elizabeth, and her mother, Vanessa Redgrave, plays the older queen. Richardson says the cast would sit and discuss the authorship debate during filming. Many were swayed, she said, by various points of Emmerich's argument: that Shakespeare was a country bumpkin with only a grammar-school education; that there's no physical evidence of his writing (even a letter); that his daughters were illiterate; that his will didn't refer to any plays or books. "All of us started to get pretty convinced," she said, including her mother, "not necessarily that it was Oxford, but that it's definitely up for debate. There are just so many missing links."

Stratfordians argue the Oxfordian theory is impossible - de Vere died in 1604, before a number of Shakespeare's most famous plays were written. Others say not so fast: Do we know when the plays were written, or are we guessing? About the will, Shapiro argues that like other wills of the time, it had a separate inventory that hasn't been found.

One of the more eloquent cases against the Stratfordian view comes from the Shakespearean actor Mark Rylance, who was artistic director of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in London for 10 years. He plays an actor in the film. "This anger about the film is bizarre, because Shakespeare has always been a mystery," he said. "It's not like Emmerich is the first person to question this. But once you really look at the man from Stratford, the mystery gets larger. Because, what we know of him just doesn't correspond to a writer's life." Rylance is one of more than 2,000 people who've signed a 2007 "The Declaration of Reasonable Doubt." about the authorship. Among his co-signers: fellow actors Derek Jacobi (also in the film) and Jeremy Irons, and two U.S. Supreme Court justices. Most important for Rylance, who believes the plays could have been a collaboration, is the idea that the inquiry is based on a deeply felt appreciation for the work.

As for Emmerich himself, he doesn't share the long history with the material that his actors do, nor did he study much Shakespeare in school in Germany. But, he said, "I was always the kid who asked, 'Why?' " So when screenwriter Orloff pitched him a script he'd written, Emmerich became fascinated with the issue; he became convinced that the man from Stratford didn't write the plays. The rest of the film, he added, is presenting hypotheses of how things might have happened - including two fringe theories about Elizabeth and her supposed out-of-wedlock children.

"I really don't know what they're afraid about," said Emmerich of his critics, especially those worried about young people. "We have the greatest actors in this film, and they're doing Shakespeare's greatest hits. We're making Shakespeare cool!" He jokes that no one is happy with him - not the Stratfordians, and not the Oxfordians. On that, he is correct. "We're a bit ambivalent about it," said Richard Malim, general secretary of the De Vere Society in Britain. "It will make a lot of people sit up, but the trouble is there's so much manifest rubbish in it that we're in fear and trembling. It's completely unnecessary."

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust is not ambivalent - it is furious. The charity, which promotes the playwright and his work, is running an online campaign to rebut the film's claims. It has also published an e-book, "Shakespeare Bites Back." And recently it blacked out Shakespeare's name on road and pub signs in his home county of Warwickshire to highlight its campaign against the movie.

All of which puzzles the actors who are realizing Emmerich's vision. "I don't see why people are threatened," Richardson said. "At the end of the day, it's all celebrating Shakespeare.">>

http://www.kansascity.com/2011/11/12/3258769/umkc-professor-applauds-shakespeare.html wrote:

UMKC professor applauds Shakespeare film ‘Anonymous’

Historian agrees with movie’s contention that plays were written by Earl of Oxford

By ROBERT TRUSSELL, The Kansas City Star

<<Felicia Hardison Londre, a respected theater historian on the faculty of the UMKC theater department, was eager to see director Roland Emmerich’s new film, “Anonymous,” and not just because it delves into the world of Elizabethan actors and playwrights. She was excited to see the movie because Emmerich and screenwriter John Orloff embrace a theory about the authorship of William Shakespeare’s plays and poetry that has been subject to disdain and outright mockery by traditionalists for decades: that the true writer was Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. That’s what Londre, a proud Oxfordian, thinks.

The idea articulated by the film is that Oxford wrote the tragedies, comedies, history plays, sonnets and narrative poems attributed to Shakespeare but, because of his social station, could not attach his name to his literary works. The film depicts Oxford hiring playwright Ben Jonson to be his front but eventually agreeing to pay Will Shakespeare, a semi-literate actor, a handsome sum for the use of his name. The film also supposes that Oxford in his youth was one of Queen Elizabeth’s lovers and that she bore him a son who became the Earl of Southampton.

Londre, who likes the film, said its impending release had been eagerly anticipated by Oxfordians, but with some trepidation. “Oxfordians were very nervous about it, mainly because they knew that it was going to use the so-called Prince Tudor theory — the idea that Southampton was Queen Elizabeth’s and de Vere’s son,” Londre said. “That is pretty much a split among Oxfordians. It hasn’t been nasty, but it is a split.”

The film also proposes that Oxford himself was Elizabeth’s offspring, making him a half-brother to his own son. In the view of some Oxfordians, Londre said, that theory pushes the limits of acceptability. “I think that’s a big risk for Oxfordians to push it that far,” she said. “So we were very, very nervous about it, but when the movie came out it actually worked because the people who make that claim in the movie are characters you’re not supposed to trust anyway. And so given that, dramatically it’s brilliant. You can have it both ways. It’s a wonderful ambiguity.”

The Stratfordians — those who think there really was a playwright and poet named William Shakespeare whose literary legacy is one of the pillars of Western civilization — give no credence to the Oxfordian argument. They contend that Shakespeare was one of those rare geniuses whose extraordinary understanding of human nature allowed him to write the plays and poems. The Oxfordians counter that Shakespeare — or, as they contend, Will Shaks-per — was a Stratford businessman who lacked the education or familiarity with the royal court to write with authority about the royal court or works based on Greek and Latin sources. The Oxfordians are accustomed to hearing their beliefs assaulted. Film critic A.O. Scott, in his review of “Anonymous” for The New York Times, put it this way: “This notion, sometimes granted the unwarranted dignity of being called a theory, is hardly new. It represents a hoary form of literary birtherism that has persisted for a century or so, in happy defiance of reason and evidence.”

Londre is, indeed, happy to discuss the Oxfordian point of view. She thinks that much of the content of Shakespeare’s poetry makes no sense unless you think Oxford was the true author. She contends that the Oxfordian argument can be supported by facts and that Stratfordians make unsupported leaps of faith, which is precisely what the Stratfordians say about the Oxfordians.

All of this raises a philosophical question: Does it matter who wrote the plays and poems? After all, there is no agreement on who Homer may have been or whether “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” could have been written by different people. Even so, those epic poems are the foundation of Western literature.

Londre was simply aghast at the question. “Of course it matters!” she said. “For many reasons. One is history itself. Why do we study history, after all? We have to learn from it. It’s been said … (that) if you get the Shakespeare authorship wrong, you get the whole Elizabethan age wrong. It tells you how they lived, how people knew each other, what books were available. A million things rest on it. Don’t we want to give credit where it’s due? We revere our artists of the past. We revere Sophocles and Michelangelo and Mozart. Doesn’t it matter that we know Mozart wrote what he did? Of course it matters.”>>