THX1138 wrote: ↑Sat Nov 05, 2022 3:43 am

Hi Ann

Do correct me where my thinking is flawed here

If the Universe keeps expanding forever and should that lead to what I've heard to be called the big rip where even atoms will be shredded, well if this is so then it fly's in the face; so to speak, of the notion that all information is lost forever once it falls into a black hole right? That is to say that one could assume that even the black holes would be torn apart during this big rip thus all the information lost within one is lost no more. I hope I stated that right but in any event that does make sense right?

I'm going to try to answer now. Warning: It's going to take time!

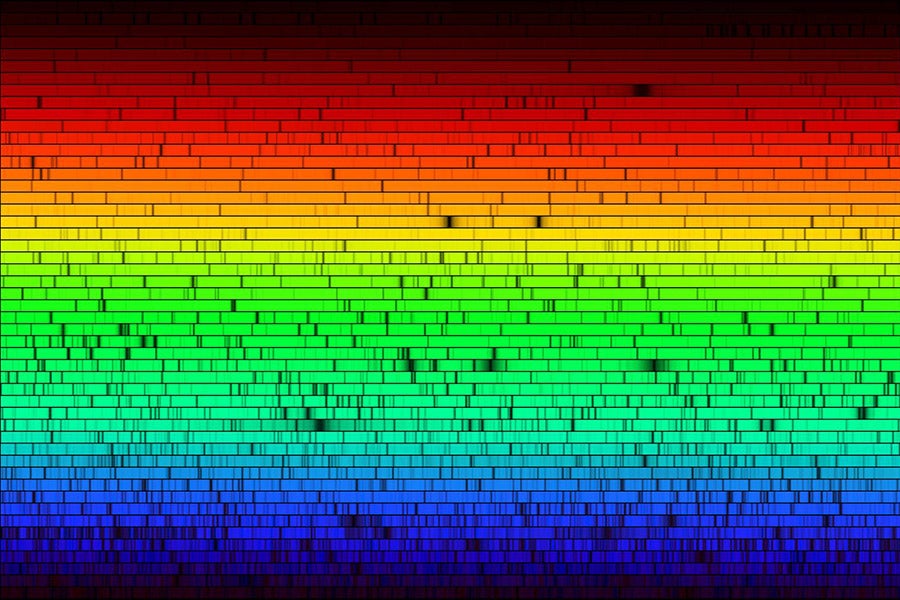

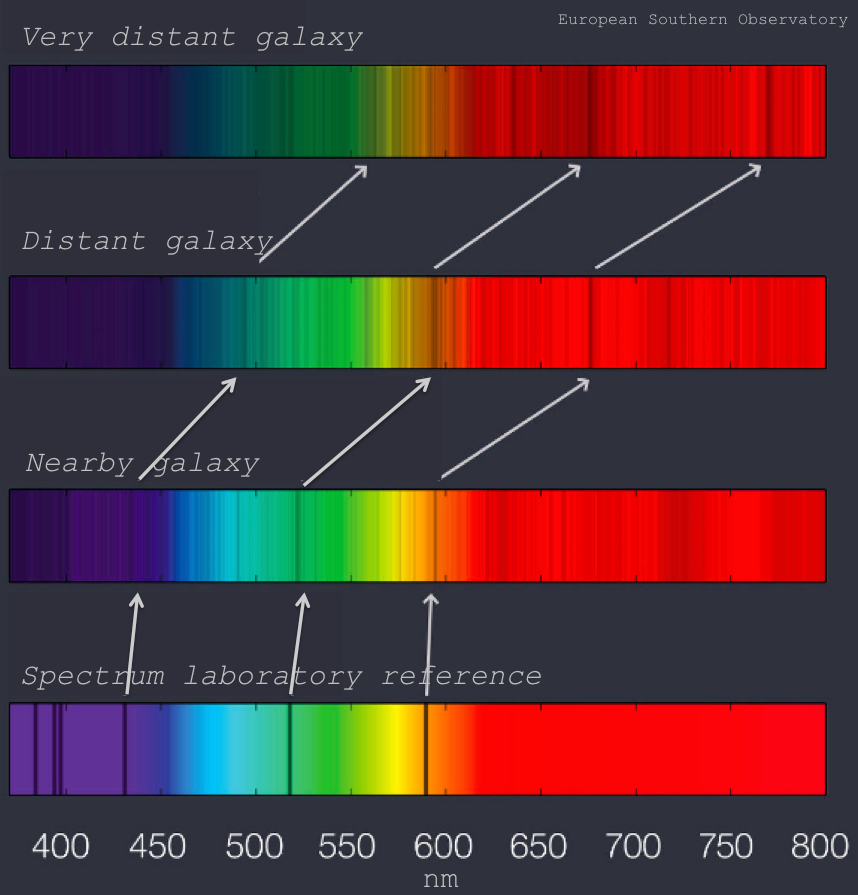

When we talk about distances in space, we have to talk about cosmological redshift. And when we talk about cosmological redshift, we have to talk about stellar spectra and spectral lines. Below are two pictures of all the colors of visible light emitted the Sun, and the position of various spectral lines:

First, what causes those spectral lines? They exist because the outer atmosphere of the Sun contains different ions of various elements, and these ions absorb very specific wavelengths of light, leaving black spaces behind. But the very same ions that absorb light from the Sun's upper atmosphere can be made to give back exactly those same wavelengths that they absorbed!

Therefore, ionized hydrogen, which leaves a black space in the Sun's spectrum at 656 nm, can be made to emit light at exactly that wavelength, 656 nm! That's why emission nebulas are red, because they glow from ionized hydrogen. And two black spaces in the yellow-orange part of the Sun's spectrum are caused by ionized sodium, and the same ionized sodium can be made to glow exactly that shade of yellow-orange in sodium lamps!

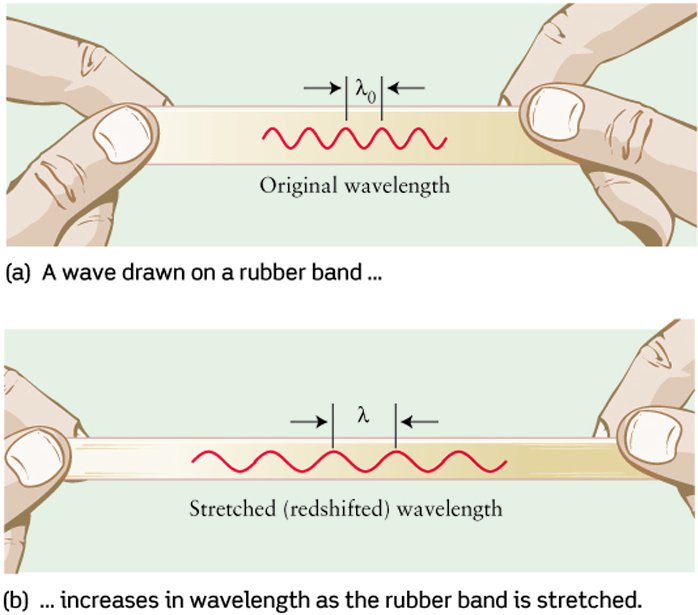

We have to go back to the spectral lines, because it is the spectral lines of galaxies that show us that the Universe is indeed expanding. It is the shifting of the spectral lines towards redder, longer wavelengths that show that the Universe is expanding. Bear in mind that light and color are really just electromagnetic waves. These waves literally get stretched to longer wavelengths by the expansion of space itself, as if space was stretching the wavelengths as if they were rubber bands!

It has been known since Edward Hubble's time in the 1920s or 30s that the Universe is expanding, but the fact that the Universe is accelerating

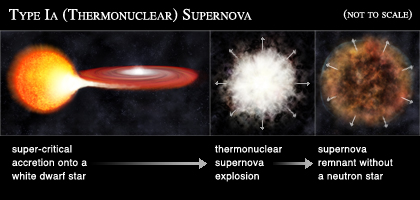

was only discovered in the 1990s. This startling fact was revealed when two astronomical teams started to search for very distant supernovas of type Ia (known as SN Ia or SNe Ia).

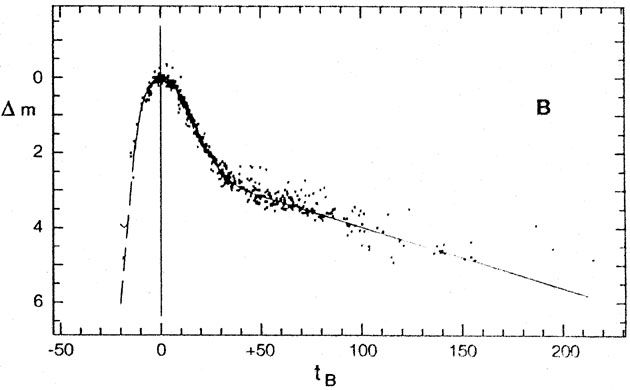

Type Ia supernovas lack hydrogen, the most common element in the Universe, in their spectra. They show a very distinctive light curve, which looks like this:

Supernovas type Ia are believed to always reach the same peak brightness. That is because they are believed to always be produced by the same kind of progenitor, a white dwarf that has lost its hydrogen envelope, and which is interacting with a companion that dumps matter on the white dwarf until it becomes too massive to sustain itself through so called electron degeneracy.

So what makes type Ia supernovas so interesting is that they explode at the same absolute brightness.

Wikipedia wrote:

The typical visual absolute magnitude of Type Ia supernovae is Mv = −19.3 (about 5 billion times brighter than the Sun), with little variation.

The cosmological redshift of a luminous object in space tells us how much the Universe has expanded since the light from this light source was emitted. But it doesn't tell us where the luminous object was when its light was emitted.

The great thing about supernovas type Ia is that astronomers can calculate how far away they were when they exploded, because they "just" have to measure the faint light that reaches us from the supernova and then calculate how far away this supernova has to be, to look as faint as it does, compared to how bright it really is known to be.

So supernovas type Ia are standard candles of the Universe. Their apparent brightness compared with their known true brightness shows astronomers how far away they were when they exploded, and their redshifts tells us how much the Universe has expanded since they exploded.

The two teams who studied distant supernovas expected to find that the Universe was decelerating, slowing down. It was believed that the Universe had received its one and only kick during the Big Bang, and then it was believed to have been slowing down ever since, because of the influence of gravity.

If the Universe had been slowing down, then the type Ia supernovas would have been rather "bright" for their distance. Because they would have moved faster in the past than they did after they exploded. They would be "closer than expected" when they exploded, if the Universe had expanded faster in the past than it does now.

So the astronomers expected to find relatively bright high redshift supernovas of type Ia. Instead, they found that the supernovas were fainter than expected, as if the Universe had picked up speed after the explosions of the distant supernovas, and the supernovas were farther away than the astronomers had thought.

But as you can see from the plot above, the Universe isn't speeding "wildly". It is accelerating very slowly. Its current acceleration puts it very close to a critical line, where the Universe is neither accelerating or decelerating. And recently, astronomers have found many more distant supernovas type Ia, which confirms the picture: Yes, the Universe is accelerating, but it isn't picking up speed in any sort of crazy manner. So astronomers really believe that there will be no Big Rip.

Ann