ESA Space Science | Rosetta | 2013 Oct 11

ESA’s comet-chasing mission Rosetta will wake up in 100 days’ time from deep-space hibernation to reach the destination it has been cruising towards for a decade.Click to play embedded YouTube video.Rosetta's twelve-year journey in space (Credit: ESA) Rosetta mission 2014-2015 milestones (Credit: ESA/AOES Medialab)Rosetta’s Philae lander on comet nucleus (Credit: ESA/AOES Medialab)

Rosetta mission 2014-2015 milestones (Credit: ESA/AOES Medialab)Rosetta’s Philae lander on comet nucleus (Credit: ESA/AOES Medialab)

Comets are the primitive building blocks of the Solar System and the likely source of much of Earth’s water, perhaps even delivering to Earth the ingredients that helped life evolve.

By studying the nature of a comet close up with an orbiter and lander, Rosetta will show us more about the role of comets in the evolution of the Solar System.

Rosetta was launched on 2 March 2004, and through a complex series of flybys – three times past Earth and once past Mars – set course to its destination: comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. It also flew by and imaged two asteroids, Steins on 5 September 2008 and Lutetia on 10 July 2010.

In July 2011 Rosetta was put into deep-space hibernation for the coldest, most distant leg of the journey as it travelled some 800 million kilometres from the Sun, close to the orbit of Jupiter. The spacecraft was oriented so that its solar wings faced the Sun to receive as much sunlight as possible, and it was placed into a slow spin to maintain stability.

Now, as both the comet and the spacecraft are on the return journey back into the inner Solar System, the Rosetta team is preparing for the spacecraft to wake up.

Rosetta’s internal alarm clock is set for 10:00 GMT on 20 January 2014.

Once it wakes up, Rosetta will first warm up its navigation instruments and then it must stop spinning to point its main antenna at Earth, to let the ground team know it is still alive.

“We don’t know exactly at what time Rosetta will make first contact with Earth, but we don’t expect it to be before about 17:45 GMT on the same day,” says Fred Jansen, ESA’s Rosetta mission manager.

“We are very excited to have this important milestone in sight, but we will be anxious to assess the health of the spacecraft after Rosetta has spent nearly 10 years in space.”

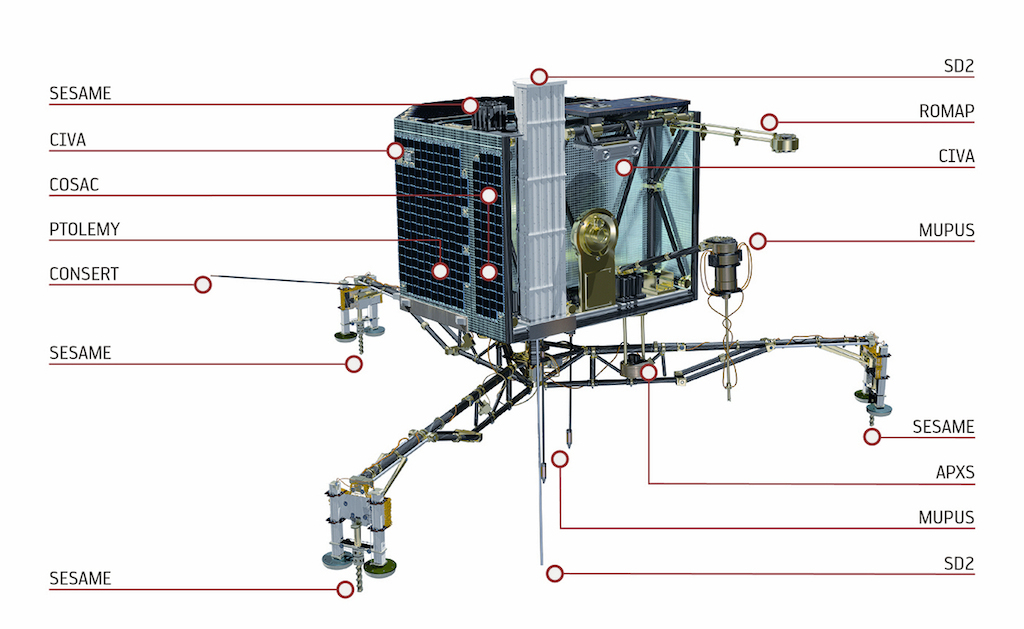

After wake-up, Rosetta will still be about 9 million km from the comet. As it moves closer, the 11 instruments on the orbiter and 10 on the lander will be turned on and checked.

In early May, Rosetta will be 2 million km from its target, and towards the end of May it will execute a major manoeuvre to line up for rendezvous with the comet in August.

The first images of a distant 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko are expected in May, which will dramatically improve calculations of the comet’s position and orbit.

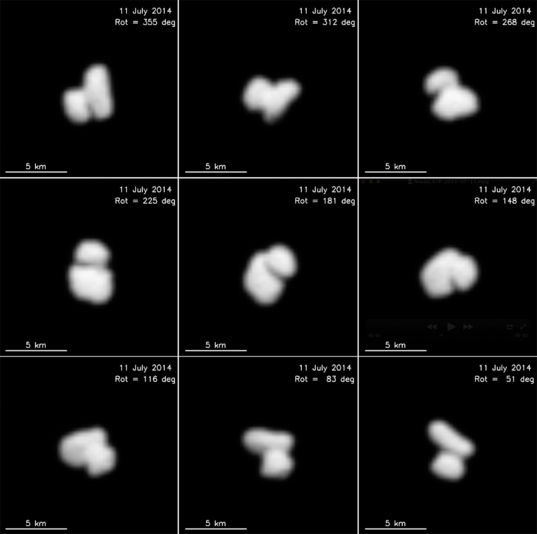

Closer in, Rosetta will take thousands of images that will provide further details of the comet’s major landmarks, its rotation speed and spin axis orientation.

Rosetta will also make important measurements of the comet’s gravity, mass and shape, and will make an initial assessment of its gaseous, dust-laden atmosphere, or coma.

Rosetta will also probe the plasma environment and analyse how it interacts with the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the solar wind.

After extensive mapping of the comet’s surface during August and September, a landing site for the 100 kg Philae probe will be chosen. It will be the first time that landing on a comet has ever been attempted.

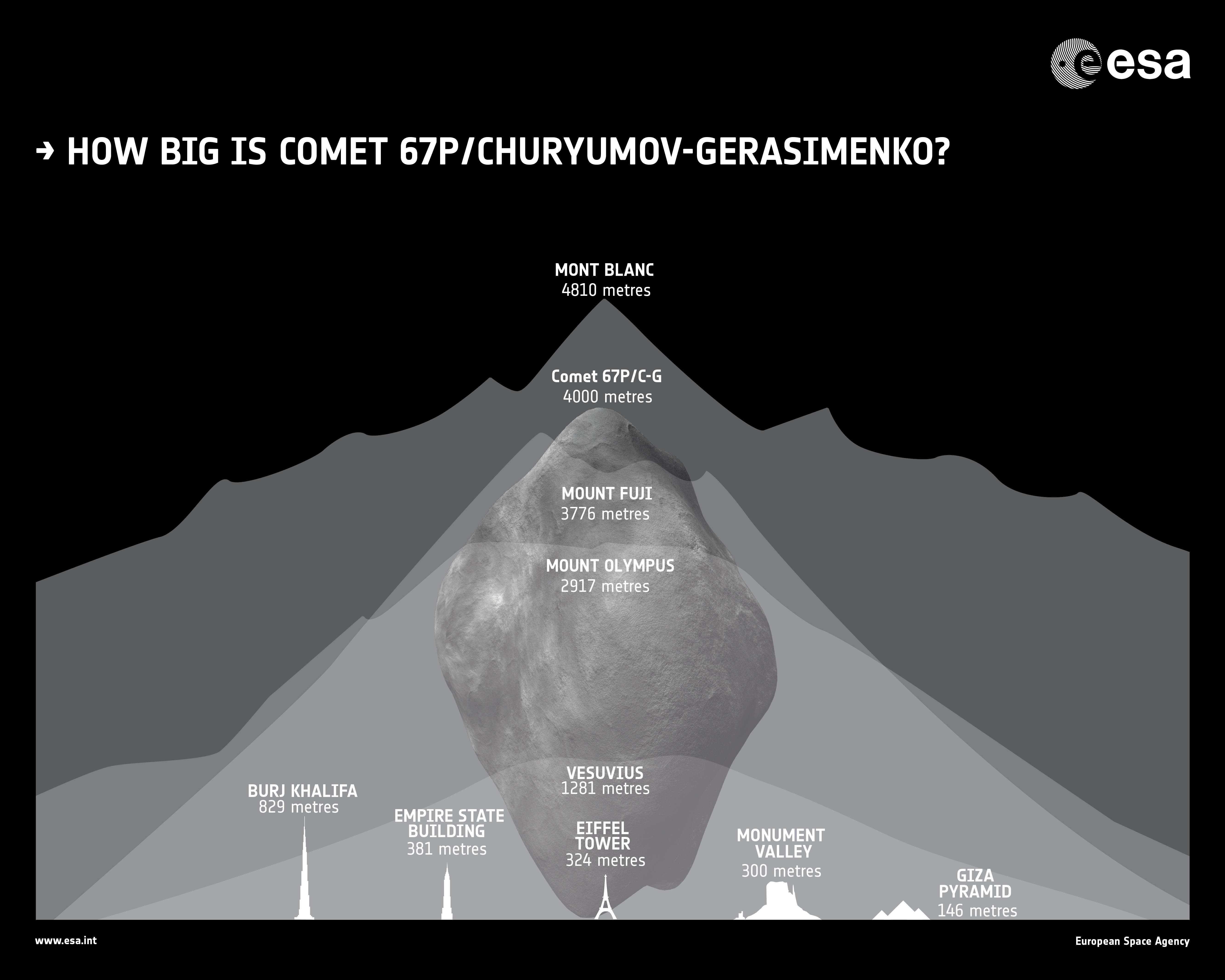

Given the almost negligible gravity of the comet’s 4 km-wide nucleus, Philae will ‘dock’ with it using ice screws and harpoons to stop it from rebounding back into space.

Philae will send back a panorama of its surroundings and very high-resolution pictures of the surface and will perform on-the-spot analysis of the composition of the ices and organic material. A drill will take samples from 20–30 cm below the surface, feeding them to the onboard laboratory for analysis.

“The focus of the mission then moves towards what we call the ‘escort’ phase, whereby Rosetta will stay alongside the comet as it moves closer to the Sun,” notes Fred.

The comet will reach its closest distance to the Sun on 13 August 2015 at about 185 million km, roughly between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

As the comet hurtles through the inner Solar System at around 100 000 km/h, the relative speed between orbiter and comet will remain equivalent to walking pace. During this ‘escort’ phase the orbiter will continue to analyse dust and gas samples while monitoring the ever-changing conditions on the surface as the comet warms up and its ices sublimate.

“This unique science period will reveal the dynamic evolution of the nucleus as never seen before, allowing us to build up a thorough description of all aspects of the comet, its local environment and revealing how it changes even on a daily basis,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist.

Rosetta will follow the comet throughout the remainder of 2015, as it heads away from the Sun and activity begins to subside.

“For the first time we will be able to analyse a comet over an extended period of time – it is not just a flyby. This will give us a unique insight into how a comet ‘works’ and ultimately help us to decipher the role of comets in the formation of the Solar System,” adds Matt.