http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rongorongo wrote:

<<Rongorongo is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Easter Island that appears to be writing or proto-writing. It cannot be read despite numerous attempts at decipherment; not even these glyphs can actually be read.

If rongorongo does prove to be writing, it could be one of as few as three or four independent inventions of writing in human history.

Two dozen wooden objects bearing rongorongo inscriptions, some heavily weathered, burned, or otherwise damaged, were collected in the late 19th century and are now scattered in museums and private collections. None remain on Easter Island. The objects are mostly tablets shaped from irregular pieces of wood, sometimes driftwood, but include a chieftain's staff, a bird-man statuette, and two reimiro ornaments. There are also a few petroglyphs which may include short rongorongo inscriptions. Oral history suggests that only a small elite was ever literate and that the tablets were sacred.

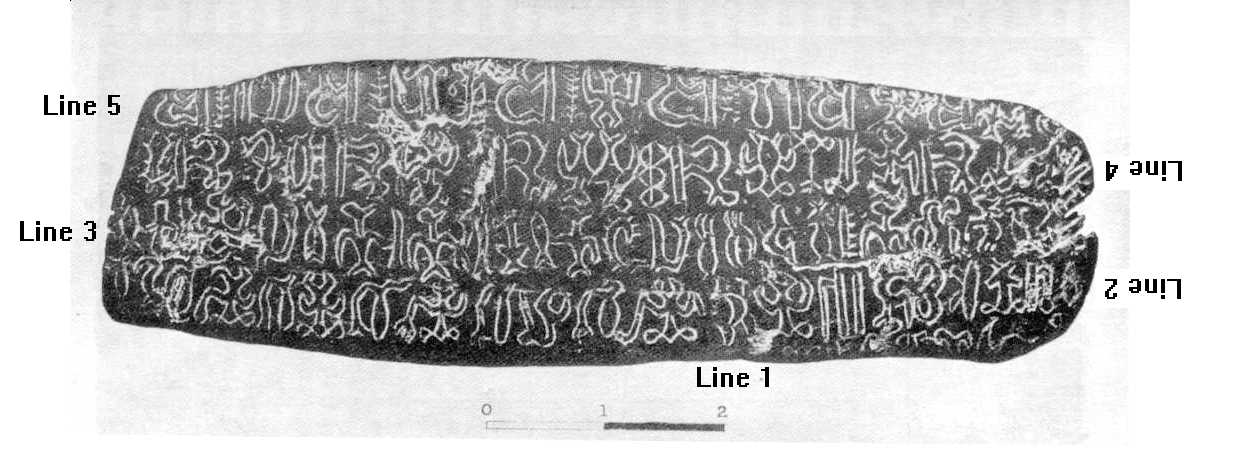

Rongorongo glyphs were written in reverse boustrophedon, left to right and bottom to top. That is, the reader begins at the bottom left-hand corner of a tablet, reads a line from left to right, then rotates the tablet 180 degrees to continue on the next line. When reading one line, the lines above and below it would appear upside down, as can be seen in the image at left. However, the writing continues onto the second side of a tablet at the point where it finishes off the first, so if the first side has an odd number of lines the second will start at the upper left-hand corner, and the direction of writing shifts to top to bottom.

The glyphs are stylized human, animal, vegetable and geometric shapes, and often form compounds. Nearly all those with heads are oriented head up and are either seen face on or in profile to the right, in the direction of writing. It is not known what significance turning a glyph head down or to the left may have had. Heads often have characteristic projections on the sides which may be eyes but which often resemble ears. Birds are common; many resemble the frigatebird which was associated with the supreme god Makemake. Other glyphs look like fish or arthropods.

Tablet Q (Small Saint Petersburg) is the sole item that has been carbon dated but the results only constrain the date to sometime after 1680. Texts A, P, and V can be dated to the 18th or 19th century by virtue of being inscribed on European oars. Orliac (2005) calculated that the wood for tablet C (Mamari) was cut from the trunk of a tree some 15 meters tall, and Easter Island has long been deforested of trees that size. Analysis of charcoal indicates that the forest disappeared in the first half of the 17th century. Roggeveen, who discovered Easter Island in 1722, described the island as "destitute of large trees."

Several scholars have suggested that rongorongo may have been a recent invention, inspired by the 1770 Spanish visit to the island and the signing of a treaty of annexation under González de Haedo. As circumstantial evidence, they note that no explorer reported the script prior to Eugène Eyraud in 1864, and that the marks with which the chiefs signed the Spanish treaty do not resemble rongorongo. Some tablets appear to have been cut with a steel blade, often rather crudely. Although steel knives were available after the arrival of the Spanish, this does cast suspicion on the authenticity of these tablets.

The hypothesis of these researchers is not that rongorongo was itself a copy of the Latin alphabet, or of any other form of writing, but that the concept of writing had been conveyed in a process anthropologists term trans-cultural diffusion, which then inspired the islanders to invent their own system of writing. If this is the case, then rongorongo emerged, flourished, fell into oblivion, and was all but forgotten within a span of less than a hundred years. However, known cases of the diffusion of writing, such as Sequoyah's invention of the Cherokee syllabary after seeing the power of English-language newspapers, involved greater contact than the signing of a single treaty.

Easter Island has the richest assortment of petroglyphs in Polynesia. Nearly every suitable surface has been carved, including the stone walls of some houses and a few of the famous mo‘ai statues and their fallen topknots. Around one thousand sites with over four thousand glyphs have been catalogued, some in bas-relief, and some painted red & white. Designs include a concentration of chimeric bird-man figures at Orongo; faces of the creation deity Makemake; marine animals like turtles, tuna, swordfish, sharks, whales, dolphins, crabs, and octopus; roosters; canoes, and over five hundred komari.

Eugène Eyraud, a lay friar of the Congrégation de Picpus, landed on Easter Island on January 2, 1864. He wrote an account of his stay in which he reports his discovery of the tablets:

"In every hut one finds wooden tablets or sticks covered in several sorts of hieroglyphic characters: They are depictions of animals unknown on the island, which the natives draw with sharp stones. Each figure has its own name; but the scant attention they pay to these tablets leads me to think that these characters, remnants of some primitive writing, are now for them a habitual practice which they keep without seeking its meaning." – Eyraud 1886:71

In 1868 the Bishop of Tahiti received a gift from the recent Catholic converts of Easter Island. It was a long cord of human hair, a fishing line perhaps, wound around a small wooden board covered in hieroglyphic writing. Stunned at the discovery, he wrote to Father Hippolyte Roussel on Easter Island to collect all the tablets and to find natives capable of translating them. But Roussel could only recover a few, and the islanders could not agree on how to read them. Yet Eyraud had seen hundreds of tablets only two years earlier. What happened to the missing tablets is a matter of conjecture. Eyraud had noted how little interest their owners had in them. Stéphen Chauvet reports that,

"As European-introduced diseases and raids by Peruvian slavers, including a final devastating raid in 1862 and a subsequent smallpox epidemic, had reduced the Rapa Nui population to under two hundred by the 1870s, it is possible that literacy had been wiped out by the time Eyraud discovered the tablets in 1866.">>