Please vote for the TWO best Astronomy Pictures of the Day (image and text) of November 20-26, 2011.

(Repeated APODs are not included in the poll.)

All titles are clickable and link to the original APOD page.

We ask for your help in choosing an APOW as this helps Jerry and Robert create "year in APOD images" review lectures, create APOM and APOY polls that can be used to create a free PDF calendar at year's end, and provides feedback on which images and APODs were relatively well received. You can select two top images for the week.

We are very interested in why you selected the APODs you voted for, and enthusiastically welcome your telling us why by responding to this thread.

Thank you!

_______________________________________________________________

<- Previous week's poll

Video Credit: Expedition 28 & 29 Crews, ISAL, NASA's JSC;

Compilation and Editing: Michael König; Music: Do Dekor (Jan Jelinek), faitiche

Historically active, this year's Leonid meteor shower was diminished by bright moonlight. Still, faithful night sky watchers did see the shower peak on November 18 and even the glare of moonlight didn't come close to masking this brilliant fireball meteor. The colorful meteor trail and final flare was captured early that morning in western skies over the Canary Island Observatorio del Teide on Tenerife. Particles of dust swept up when planet Earth passes near the orbit of periodic comet Tempel-Tuttle, Leonid meteors typically enter the atmosphere at nearly 70 kilometers per second. Looking away from the Moon, the wide angle camera lens also recorded bright stars in the familiar constellations Orion and Taurus near picture center. Inset are two exposures of this fireball's persistent train. The consecutive train images follow the meteor's flash by several minutes as high altitude winds disperse the faint, smokey trail. The two large telescope buildings are the GREGOR telescope with reddish dome and the Vacuum Tower Telescope along the right edge of the frame, both sun watching telescopes.

From an altitude of over 5,000 meters, the night sky view from Chajnantor Plateau in the Chilean Andes is breathtaking in more ways than one. The dark site's rarefied atmosphere, at about 50 percent sea level pressure, is also extremely dry. That makes it ideal for the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) designed to explore the universe at wavelengths over 1,000 times longer than visible light. Near the center of the the panoramic scene, ALMA's 7 and 12 meter wide dish antennas are illuminated by a young Moon nestled in the arc of the Milky Way. ALMA's antenna configurations are intended to achieve a resolution comparable to space telescopes by operating as an interferometer. At left, a meteor's streak and the Milky Way's satellite galaxies, the Large (bottom) and Small Magellanic Clouds grace the night.

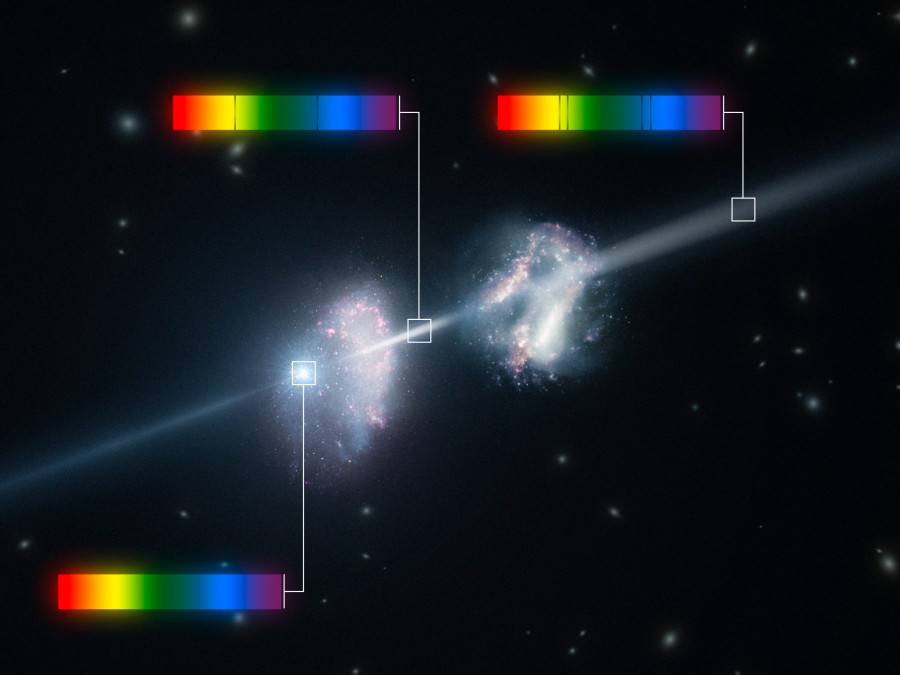

In this artist's illustration, two distant galaxies formed about 2 billion years after the big bang are caught in the afterglow of GRB090323, a gamma-ray burst seen across the Universe. Shining through its own host galaxy and another nearby galaxy, the alignment of gamma-ray burst and galaxies was inferred from the afterglow spectrum following the burst's initial detection by the Fermi Gamma Ray Space Telescope in March of 2009. As seen by one of the European Southern Observatory's very large telescope units, the spectrum of the burst's fading afterglow also offered a surprising result - the distant galaxies are richer in heavy elements than the Sun, with the highest abundances ever seen in the early Universe. Heavy elements that enrich mature galaxies in the local Universe were made in past generations of stars. So these young galaxies have experienced a prodigious rate of star formation and chemical evolution compared to our own Milky Way. In the illustration, the light from the burst site at the left passes successively through the galaxies to the right. Spectra illustrating dark absorption lines of the galaxies' elements imprinted on the afterglow light are shown as insets. Of course, astronomers on planet Earth would be about 12 billion light-years off the right edge of the frame.

A tantalizing glimpse inside this dome was captured after sunset at the mountain top Pic Du Midi Observatory in the French Pyrenees. But while most are just beginning their work at sunset, this observatory's day was done. The instrument looming within is CLIMSO (for Christian Latouche IMageur Solaire), dedicated to exploring dynamic phenomena across the surface and atmosphere of the Sun. To image the solar atmosphere or corona, CLIMSO uses coronographs. Developed by French astronomer Bernard Lyot in the 1930s, coronographs block light from the center of the telescope beam to create an artificial solar eclipse and allow a continuous view of the solar corona. In this surreal twilight scene above a sea of clouds, the dome's interior was revealed by the single, long exposure as the open slit rotated across the field of view.

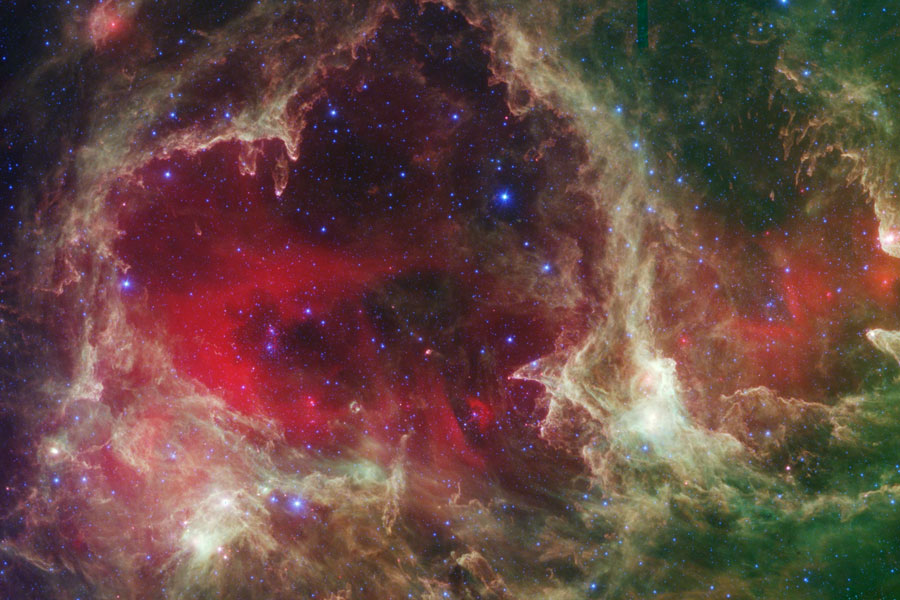

The prominent ridge of emission featured in this vivid skyscape is designated IC 5067. Part of a larger emission nebula with a distinctive shape, popularly called The Pelican Nebula, the ridge spans about 10 light-years and follows the curve of the cosmic pelican's head and neck. The Pelican Nebula close-up was constructed from narrowband data mapping emission from sulfur, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms to red, green, and blue colors. Fantastic, dark shapes inhabiting the view are clouds of cool gas and dust sculpted by energetic radiation from young, hot, massive stars. But stars are also forming within the dark shapes. In fact, twin jets emerging from the tip of the long, dark tendril below center are the telltale signs of an embedded protostar cataloged as Herbig-Haro 555. The Pelican Nebula itself, also known as IC 5070, is about 2,000 light-years away. To find it, look northeast of bright star Deneb in the high flying constellation Cygnus.

<- Previous week's poll