Discover Blogs | Bad Astronomy | 2011 Aug 25

Attention all astronomers! There is a new Type Ia supernova that has been seen in the nearby spiral galaxy M101, and it’s very young — currently only about a day old! This is very exciting news; getting as much data on this event as possible is critical.

Most likely professional astronomers are already aware of the supernova, since observations have already been taken by Swift (no X-rays have yet been seen, but it’s early yet) and Hubble observations have been scheduled. Still, I would urge amateur astronomers to take careful observations of the galaxy.

[As an aside, I'll note that this supernova won't get bright enough to see naked eye and poses no threat at all to us here on Earth. It may be visible in decent-sized telescopes, though, and as you'll see this may be a very important event in the annals of astronomy.]

So why is this a big deal?

First of all, a supernova is an exploding star — one of the most violent events in the Universe. There are different kinds of supernovae, but a Type Ia occurs, it’s thought, when a superdense white dwarf — the remnant core of a dead star — siphons material off a companion star. If enough material piles on top of the white dwarf, it can suddenly start to fuse hydrogen into helium. This starts a runaway effect, and the entire star explodes. This supernova can release so much energy it can actually outshine its host galaxy! If you want more details, I’ve written about Type Ia supernovae before: Astronomers spot ticking supernova time bomb and Dwarf merging makes for an explosive combo.

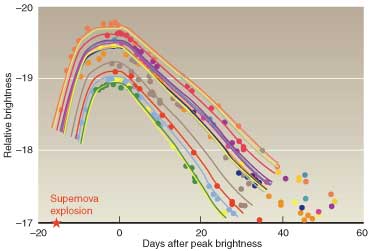

So this kind of supernova is incredibly bright, making them easy to spot over vast distances. These events are very important, because we think that each Type Ia supernova is very similar in the way it explodes, making them useful as benchmarks in gauging distances to very distant galaxies. In fact, it is the study of these explosions that has helped us nail down how fast the Universe is expanding, and also led to the discovery of dark energy. Clearly, the more we know about them, the better.

M101 is a spiral galaxy only about 25 million light years away, making it one of the closest big spirals in the sky. It’s also huge, boasting a trillions stars, ten times the mass of our Milky Way. You can read all about it in an earlier post featuring the image at the top of this article.

Given M101′s close distance, this new supernova will be relatively easy to study. And the best part is that the exploding star was caught young: most of the ones we see are far away, and too faint to be seen until they start to reach their maximum brightness after a few days. Getting data on them early is absolutely critical for understanding them, and it’s the hardest part of all this. I am not exaggerating to say this new supernova could be a linchpin in our understanding of these events.

Interestingly, Hubble took images of this galaxy in 2002, and astronomers dug up the archived images and looked at the spot of the supernova to see if anything was there back then. Nothing shows up in the blue filter, but in the red (shown here) there are two stars very close to the position of the future supernova (the circle is centered on the best measurement of the supernova’s position). From their brightness and color, both of these stars are red giants, stars like the Sun but near the ends of their lives. That would fit with the Type Ia supernova: red giants are so big that if there’s a white dwarf nearby, it could suck up their matter and start the chain of events that led to its doom. Further observations may pin this down. If one of these stars is what fed the supernova, that’s seriously cool; there are only a handful of supernova progenitor stars that have ever been seen*.

All in all, this is pretty much a big deal. The galaxy is close, pretty, a bit odd, and is hosting the nearest Type Ia supernova seen in decades which was caught when it was less than a day old. I’m excited! I know a lot of telescopes will be aimed at the northern skies over the next few days, and I’ll be very interested to find out what they see.

Nearest supernova of its type in 40 years, say scientists

University of Oxford | 2011 Aug 25

Astronomers last night discovered a bright supernova, otherwise known as an exploding star, and say it is the nearest of its type observed for 40 years.

The supernova was spotted in the Pinwheel Galaxy, M101, a spiral galaxy a mere 21 million light years away, lying in the famous constellation of the Great Bear (Ursa Major).

Scientists from the University of Oxford made the discovery with their colleagues from the Palomar Transient Factory (PTF) collaboration, using a robotic telescope in California in the United States.

Oxford team leader, Dr Mark Sullivan, said: 'The most exciting thing is that this is what's known as a type 1a supernova - the kind we use to measure the expansion of the Universe. Seeing one explode so close by allows us to study these events in unprecedented detail.'

The supernova, dubbed PTF11kly, is still getting brighter, and the team's best guess is that it might even be visible with good binoculars in ten days' time, appearing brighter than any other supernova of its type in the last 40 years.

Dr Sullivan said; 'The best time to see this exploding star will be just after evening twilight in the Northern hemisphere in a week or so's time. You'll need dark skies and a good pair of binoculars, although a small telescope would be even better.'

Following the discovery, which was made at 8pm UK time last night, astronomers around the world were scrambled to get follow up images and data. Among the first to respond, within 90 minutes, was the robotic 2m Liverpool Telescope, located in the Canary Islands.

The team will be watching carefully over the next few weeks, and hope to use NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to study the supernova's chemistry and physics.The scientists in PTF have discovered more than 1,000 supernovae since it started operating in 2008, but they believe this could be their most significant discovery yet. The last time a supernova of this sort occurred so close was in 1972.

'Before that, you'd have to go back to 1937, 1898, and 1572 to find more nearby Type 1a supernovae,' said Professor Peter Nugent, from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the USA. 'Observing PTF 11kly unfold should be a wild ride. It is an instant cosmic classic.'

The Palomar Transient Factory is a wide-field survey operated at the Palomar Observatory by the California Institute of Technology on behalf of a worldwide consortium of partner institutions. Collaborating institutions are Caltech, Columbia University, Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, UC Berkeley, University of Oxford, and the Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel).

Berkeley Scientists Discover an “Instant Cosmic Classic” Supernova

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | 2011 Aug 25

Supercomputing, fast networks key to early discovery of explosion

A supernova discovered yesterday is closer to Earth — approximately 21 million light-years away — than any other of its kind in a generation. Astronomers believe they caught the supernova within hours of its explosion, a rare feat made possible with a specialized survey telescope and state-of-the-art computational tools.

- [i]These images show Type Ia supernova PTF 11kly, the youngest ever detected—over the past three nights. The left image taken on August 22 shows the event before it exploded supernova, approximately 1 million times fainter than the human eye can detect. The center image taken on August 23 shows the supernova at about 10,000 times fainter than the human eye can detect. The right image taken on August 24 shows that the event is 6 times brighter than the previous day. In two weeks time it should be visible with a good pair of binoculars. (Credit: PTF Collaboration)[/i]

The finding of such a supernova so early and so close has energized the astronomical community as they are scrambling to observe it with as many telescopes as possible, including the Hubble Space Telescope.

Joshua Bloom, assistant professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, called it “the supernova of a generation.” Astronomers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and UC Berkeley, who made the discovery predict that it will be a target for research for the next decade, making it one of the most-studied supernova in history.

The supernova, dubbed PTF 11kly, occurred in the Pinwheel Galaxy, located in the “Big Dipper,” otherwise known as the Ursa Major constellation. It was discovered by the Palomar Transient Factory (PTF) survey, which is designed to observe and uncover astronomical events as they happen.

“We caught this supernova very soon after explosion. PTF 11kly is getting brighter by the minute. It’s already 20 times brighter than it was yesterday,” said Peter Nugent, the senior scientist at Berkeley Lab who first spotted the supernova. Nugent is also an adjunct professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley. “Observing PTF 11kly unfold should be a wild ride. It is an instant cosmic classic.”

He credits supercomputers at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a Department of Energy supercomputing center at Berkeley Lab, as well as high-speed networks with uncovering this rare event in the nick of time.

The PTF survey uses a robotic telescope mounted on the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory in Southern California to scan the sky nightly. As soon as the observations are taken, the data travels more than 400 miles to NERSC via the National Science Foundation’s High Performance Wireless Research and Education Network and DOE’s Energy Sciences Network (ESnet). At NERSC, computers running machine learning algorithms in the Real-time Transient Detection Pipeline scan through the data and identify events to follow up on. Within hours of identifying PTF 11kly, this automated system sent the coordinates to telescopes around the world for follow-up observations.

Three hours after the automated PTF pipeline identified this supernova candidate, telescopes in the Canary Islands (Spain) had captured unique “light signatures,” or spectra, of the event. Twelve hours later, his team had observed the event with a suite of telescopes including the Lick Observatory (California), and Keck Observatory (Hawaii) had determined the supernova belongs to a special category, called Type Ia. Nugent notes that this is the earliest spectrum ever taken of a Type Ia supernova.

“Type Ia supernova are the kind we use to measure the expansion of the Universe. Seeing one explode so close by allows us to study these events in unprecedented detail,” said Mark Sullivan, the Oxford University team leader who was among the first to follow up on this detection.

“We still do not know for sure what causes such explosions,” said Weidong Li, senior scientist at UC Berkeley and collaborator of Nugent. “We are using images from the Hubble Space Telescope, taken fortuitously years before an explosion to search for clues to the event’s origin.”

The team will be watching carefully over the next few weeks, and an urgent request to NASA yesterday means the Hubble Space Telescope will begin studying the supernova’s chemistry and physics this weekend.

Catching supernovae so early allows a rare glimpse at the outer layers of the supernova, which contain hints about what kind of star exploded. “When you catch them this early, mixed in with the explosion you can actually see unburned bits from star that exploded! It is remarkable,” said Andrew Howell of UC Santa Barbara/Las Cumbres Global Telescope Network. “We are finding new clues to solving the mystery of the origin of these supernovae that has perplexed us for 70 years. Despite looking at thousands of supernovae, I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

“The ability to process all of this data in near real-time and share our results with collaborators around the globe through the Science Gateway at NERSC is an invaluable tool for following up on supernova events,” says Nugent. “We wouldn’t have been able to detect and observe this candidate as soon as we did without the resources at NERSC.”

At a mere 21 million light-years from Earth, a relatively small distance by astronomical standards, the supernova is still getting brighter, and might even be visible with good binoculars in ten days’ time, appearing brighter than any other supernova of its type in the last 30 years.

“The best time to see this exploding star will be just after evening twilight in the Northern hemisphere in a week or so,” said Oxford’s Sullivan. “You’ll need dark skies and a good pair of binoculars, although a small telescope would be even better.”

The scientists in the PTF have discovered more than 1,000 supernovae since it started operating in 2008, but they believe this could be their most significant discovery yet. The last time a supernova of this sort occurred so close was in 1986, but Nugent notes that this one was peculiar and heavily obscured by dust.

”Before that, you’d have to go back to 1972, 1937 and 1572 to find more nearby Type Ia supernovae,” says Nugent.

'Once in a Generation' Supernova Discovered

University of California, Santa Barbara | 2011 Aug 25

Shiny and New Supernova Spotted in Nearby Galaxy

Universe Today | Jason Major | 2011 Aug 25

Possible Type-Ia Supernova in M101

Universe Today | Tammy Plotner | 2011 Aug 25

Supernova Erupts in Pinwheel Galaxy

Sky & Telescope | Kelly Beatty | 2011 Aug 25

M101 supernova update

Discover Blogs | Bad Astronomy | 2011 Aug 25

Closest Supernova in 25 Years Is a 'Cosmic Classic'

Space/com | 2011 Aug 26

Exploding star coming to a telescope near you

New Scientist | David Shiga | 2011 Aug 26

Uncovering the Secrets of the Great Supernova

W. M. Keck Observatory | 2011 Aug 26

APOD: A Young Supernova in the Nearby Pinwheel Galaxy (2011 Aug 26)

http://asterisk.apod.com/viewtopic.php?f=9&t=25056