Thanks, Owlice!

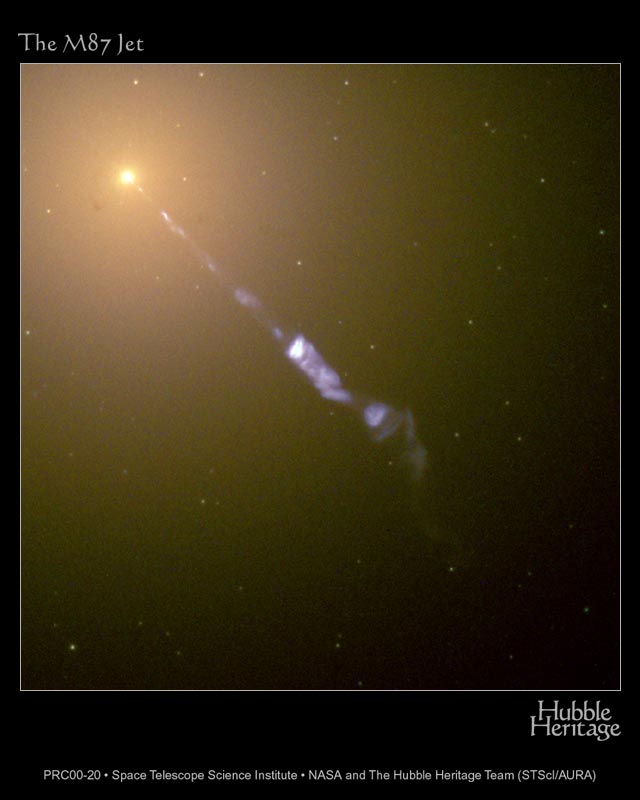

It is not hard to imagine that present-day mergers may create "super star clusters" that may evolve into future globulars. Owlice's third link showed Hubble pictures of massive young clusters in NGC 4038, which have formed out of the collision between NGC 4038 and 4039. Another example is Stephan's Quintet:

The colliding yellow galaxies on the right, NGC 7318a and 7318b, are surrounded by a huge "ring" of violently expelled gas which has fragmented and formed large numbers of bright blue clusters. Some of these clusters are undoubtedly very massive. (The galaxy at lower left is a foreground object.)

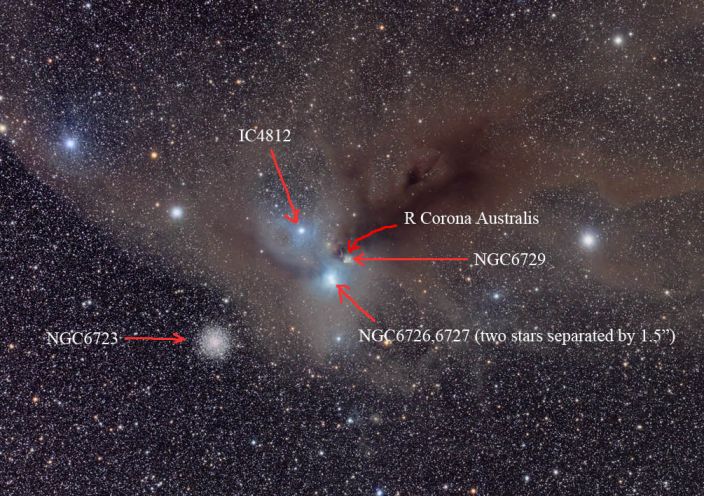

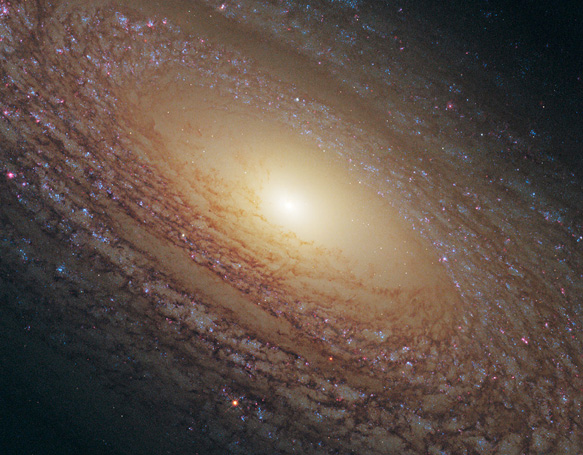

Bright and massive clusters can form also in galaxies which are not colliding or merging. A favorite example of mine is the super star cluster in NGC 6946. A portrait of this galaxy was Astronomy Picture of the Day on January 25, 2005:

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap050125.html

The super star cluster stands out at eleven o'clock in the image above. Here is a closeup of the cluster:

http://www.astro.uu.nl/siu/people/N6946PC.GIF

While the super star cluster is a unique object in NGC 6946, the galaxy is forming stars at a high rate, and it is producing a very remarkable number of supernovae. My software mentions six supernovae in NGC 6946 between 1917 and 1980, but I'm sure there have been at least two more since 1980. Typcially for a galaxy which is currently or has recently produced a lot of stars, NGC 6946 is quite dusty. Its far infrared magnitude is two magnitudes brighter than its blue magnitude, which is quite a lot for a face-on galaxy. The APOD caption suggested, as you could see, that a possible reason for the high rate of star formation of NGC 6946 might be the accretion of gas clouds from the surrounding region.

Our closest galactic neighbour, the Large Magellanic Cloud, also has a at least one super star cluster, R136:

The Large Magellanic Cloud is forming large numbers of stars. The more richly starforming a galaxy is, the greater the chance that it will form at least one really massive cluster. Sidney van den Bergh wrote in the paper that Owlice gave us a link to:

These data show that the fraction of the U light of galaxies that is generated

by young clusters is proportional to the rate of star formation per unit area to the power

~1.2. This result suggests that the present specific cluster frequency in galaxies will, to a

large extent, be determined by the peak rate of star formation per unit area during their

evolutionary history. The high S values observed in some central galaxies of rich clusters

might therefore be due to a high surface density of star formation early in their history.

By the same token the observation that elliptical galaxies have higher mean S values than

spirals may be interpreted to mean that the peak rate of star formation in E galaxies was

higher than that in disk galaxies.

Here van den Bergh says that richly starforming galaxies will stand a better chance to form a really large cluster. He also says that the peak rate of star formation in elliptical galaxies was higher than in disk galaxies, which agrees with what I said earlier about many elliptical galaxies having started out as ULIRGs, Ultra Luminous Infrared Galaxies, which were once extremely dusty because of their incredible star formation.

As for the Large Magellanic Cloud, it has apparently never been a very early ULIRG. It does not show any signs of very early extreme star formation. Sidney van den Bergh has shown earlier that the LMC experienced some star formation very long ago, about twelve billion years or so, but then it was more or less quiet for billions of years. However, a few billion years ago it started forming stars again, and about two billion years ago this star formation seems to have peaked, according to van den Bergh, although star formation is still vigorous in the LMC. What happened to this galaxy to turn it into such a star factory so suddenly? Clearly the LMC is interacting quite strongly with the SMC, the Small Magellanic Cloud, and it could be that this interaction started when the star formation of the LMC picked up. But the Magellanic clouds are obviously affected by their close proximity to the Milky Way, too. But the Magellanic galaxies appear not to have been "original" satellites of the Milky Way, and they may not be true satellites of the Milky Way even today. They are apparently passing us by at a high speed, too high for them to be gravitationally bound to us.

Anyway the interaction between the LMC and both the SMC and the Milky Way has definitely made star formation inside the LMC increase. And because it is forming so many stars, it can also find a few truly massive clusters. Wikipedia writes about R136, the most massive young cluster of the LMC:

One of the stars, R136a1, is the most massive star found to date with 265 solar masses,[7] as well as the most luminous at 10,000,000 times the brightness of the Sun.[8] R136 produces most of the energy that makes the Tarantula Nebula visible. The estimated mass of the cluster is 450,000 solar masses, suggesting it will probably become a globular cluster in the future.[9]

So the estimated mass of the cluster is 450,000 solar masses. While impressive, that is not an overwhelmingly large mass after all, not compared with old globular clusters. Wikipedia says that Omega Centauri, the largest globular of our own galaxy, contains an estimated mass of 5,000,000 solar masses. Of course, Omega Centauri may be a special case, since it may not be a "true" single-generation globular cluster, but instead it might be a captured dwarf galaxy. If so, what is left of that dwarf galaxy now is the bulge, which would now orbit the Milky Way mimicking as a globular cluster. So Omega Centauri might not be fully comparable to other globular clusters. However, a "true" and massive MIlky Way globular like M13 contains an estimated 600,000 solar masses, and M13 is one of those truly ancient globulars, only slightly younger than the universe. When R136 gets to be thirteen billion years old, it will most certainly have lost much of its mass. So while R136 is dazzlingly bright by today's standards, M13 was much more dazzling and fantastic at the dawn of time when it was born.

I'll be back with more here, I think.

Ann