http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Opabinia_BW2.jpg/220px-Opabinia_BW2.jpg wrote:

Cambrian Opabinia's closest living relative: The tardigrades

Cambrian Opabinia's closest living relative: The tardigrades

<<Tardigrades (commonly known as water bears or moss piglets) form the phylum Tardigrada, part of the superphylum Ecdysozoa. They are microscopic, water-dwelling, segmented animals with eight legs. Tardigrades were first described by Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773 (kleiner Wasserbär = little water bear). The name Tardigrada means "slow walker" and was given by Lazzaro Spallanzani in 1777. The name water bear comes from the way they walk, reminiscent of a bear's gait. The biggest adults may reach a body length of 1.5 millimetres, the smallest below 0.1 mm. Freshly hatched larvae may be smaller than 0.05 mm.

Tardigrades are polyextremophiles; scientists have reported their existence in hot springs, on top of the Himalayas, under layers of solid ice and in ocean sediments. Many species can be found in a milder environment like lakes, ponds and meadows, while others can be found in stone walls and roofs. Tardigrades are most common in moist environments, but can stay active wherever they can retain at least some moisture.

Tardigrades have been known to withstand the following extremes while in this state:

- * Temperature – tardigrades can survive being heated for a few minutes to 151 °C, or being chilled for days at -200 °C, or for a few minutes at -272 °C (~1 degree above absolute zero).

* Pressure – they can withstand the extremely low pressure of a vacuum and also very high pressures, more than 1,200 times atmospheric pressure. It has recently been demonstrated that tardigrades can survive the vacuum of open space and solar radiation combined for at least 10 days. Recent research has revealed that they can also withstand pressure of 6,000 atmospheres, which is nearly six times the pressure of water in the deepest ocean trench.

* Dehydration – tardigrades have been shown to survive nearly 10 years in a dry state. When encountered by extremely low temperatures, their body composition goes from 85% water to only 3%. As water expands upon freezing, dehydration ensures the tardigrades do not get ripped apart by the freezing ice (as waterless tissues cannot freeze).

* Radiation – tardigrades can withstand median lethal doses of 5,000 Gy (gamma-rays) and 6,200 Gy (heavy ions) in hydrated animals (5 to 10 Gy could be fatal to a human). The only explanation thus far for this ability is that their lowered water state provides fewer reactants for the ionizing radiation.In September 2007, a space launch (Foton-M3) showed that tardigrades can survive the extreme environment of outer space for 10 days. After being rehydrated back on Earth, over 68% of the subjects protected from high-energy UV radiation survived and many of these produced viable embryos, and a handful survived full exposure to solar radiation.

* Environmental toxins – tardigrades can undergo chemobiosis—a cryptobiotic response to high levels of environmental toxins. However, these laboratory results have yet to be verified.

Tardigrades are one of the few groups of species that are capable of reversibly suspending their metabolism and going into a state of cryptobiosis. Several species regularly survive in a dehydrated state for nearly ten years. Depending on the environment they may enter this state via anhydrobiosis, cryobiosis, osmobiosis or anoxybiosis. While in this state their metabolism lowers to less than 0.01% of normal and their water content can drop to 1% of normal. Their ability to remain desiccated for such a long period is largely dependent on the high levels of the non-reducing sugar trehalose, which protects their membranes. In this cryptobiotic state the tardigrade is known as a tun.

More than 1,000 species of tardigrades have been described. The most convenient place to find tardigrades is on lichens and mosses. Other environments are dunes, beaches, soil, and marine or freshwater sediments, where they may occur quite frequently (up to 25,000 animals per litre). Tardigrades often can be found by soaking a piece of moss in spring water. Siberian tardigrades differ from living tardigrades in several ways. They have three pairs of legs rather than four; they have a simplified head morphology; and they have no posterior head appendages. It is considered that they probably represent a stem group of living tardigrades. Tardigrades are eutelic, with all adult tardigrades of the same species having the same number of cells. Some tardigrade species have as many as about 40,000 cells in each adult's body, others have far fewer. Most tardigrades are phytophagous (plant eaters) or bacteriophagous (bacteria eaters), but some are predatory (e.g., Milnesium tardigradum).

The tardigrade body has four segments (not counting the head), four pairs of legs without joints, and feet with four to eight claws each. The cuticle contains chitin and is moulted periodically. The tubular mouth is armed with stylets, which are used to pierce the plant cells, algae, or small invertebrates on which the tardigrades feed, releasing the body fluids or cell contents. The mouth opens into a triradiate, muscular, sucking pharynx. The stylets are lost when the animal moults, and a new pair is secreted from a pair of glands that lie on either side of the mouth. The pharynx connects to a short oesophagus, and then to an intestine that occupies much of the length of the body, which is the main site of digestion. The intestine opens, via a short rectum, to an anus located at the terminal end of the body. Some species only defecate when they moult, leaving the faeces behind with the shed cuticle.

Although some species are parthenogenetic, both males and females are usually present, each with a single gonad located above the intestine. Two ducts run from the testis in males, opening through a single pore in front of the anus. In contrast, females have a single duct opening either just above the anus or directly into the rectum, which thus forms a cloaca.

Tardigrades are oviparous, and fertilisation is usually external. Mating occurs during the moult with the eggs being laid inside the shed cuticle of the female and then covered with sperm. A few species have internal fertilisation, with mating occurring before the female fully sheds her cuticle. In most cases, the eggs are left inside the shed cuticle to develop, but some attach them to the nearby substrate. The eggs hatch after no more than fourteen days, with the young already possessing their full complement of adult cells. Growth to the adult size therefore occurs by enlargement of the individual cells (hypertrophy), rather than by cell division. Tardigrades live for three to thirty months, and may moult up to twelve times.

Recent DNA and RNA sequencing data indicate that tardigrades are the sister group to the arthropods and Onychophora. These groups have been traditionally thought of as close relatives of the annelids, but newer schemes consider them Ecdysozoa, together with the roundworms (Nematoda) and several smaller phyla.Tardigrade genomes vary in size, from about 75 to 800 megabase pairs of DNA. The genome of a tardigrade species, Hypsibius dujardini, is being sequenced at the Broad Institute. Hypsibius dujardini has a compact genome and a generation time of about two weeks, and it can be cultured indefinitely and cryopreserved.>>

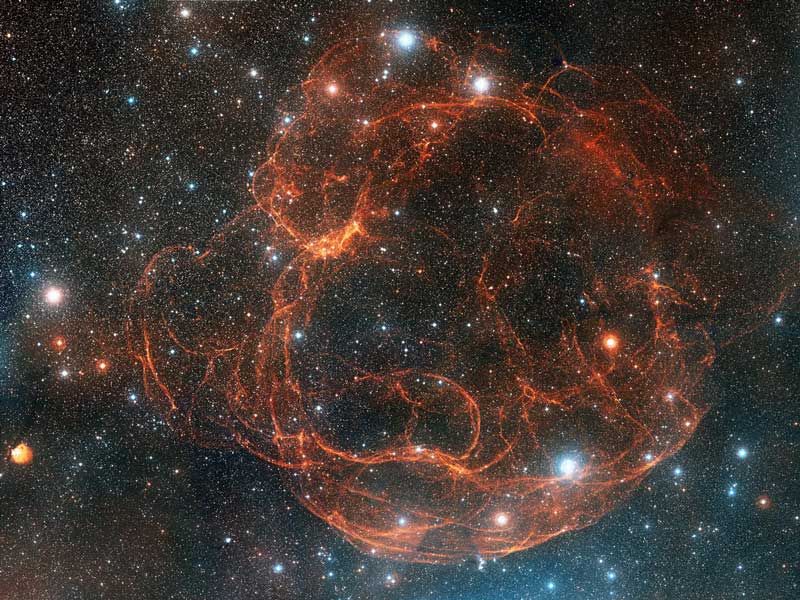

Simeis 147: Supernova Remnant

Simeis 147: Supernova Remnant