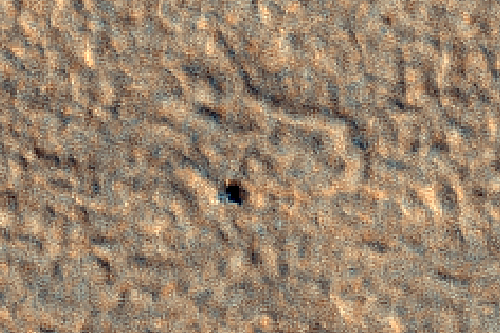

The latest HiRISE image appears to show that a solar panel of the Phoenix lander has collapsed.

HiRISE has been imaging the terrain around the landing site, including the Phoenix spacecraft itself, to study the seasonal changes that occur around this region. Phoenix landed on 25 May 2008 at 68 degrees North latitude during the Martian summer.

In the winter at this latitude the atmosphere and surface get so cold that carbon dioxide, which accounts for 95 percent of the gas in the Martian atmosphere, forms a frost on the surface as much as several decimeters (one or more feet) thick. This frost, also known as dry ice, blankets the entire northern landscape each winter, including any spacecraft that might be on the surface. In spring and summer this frost dissipates by sublimation, the process in which a solid ice evaporates directly to a gas without any melting.

This new image of the Phoenix landing site is a close match to the season and illumination and viewing angles of some of the first HiRISE images acquired after the successful landing on 25 May 2008. By comparison to

PSP_009290_2485 (and

other images acquired in 2008) we can see that the lander, heat shield, and backshell-plus-parachute are now covered by dust, so they lack the distinctive colors of the hardware or the surfaces where the pre-landing dust was disturbed.

But if the lander is structurally intact, it should cast the same shadows. While that is indeed the case for the shadow cast by the backshell (which came to rest on its side), that does not appear to be the case for the lander.

The 2008 lander images showed a very bright spot (from specular reflections) with relatively blue spots on either side corresponding to the clean circular solar panels. The shadows cast by the lander body and solar panels consists of three overlapping dark circles (

see simulated image), although the specular reflection hides part of the shadows and the three shadows will merge together to a degree in actual HiRISE images.

In this observation, with illumination and viewing angles within 1 degree of those in

PSP_009290_2485, we see a dark shadow that could be that of the lander body and eastern solar panel, but no shadow from the western solar panel is apparent. Because the specular reflection is no longer present on the dusty lander, the 2010 image should provide a better view of the of the west-array shadow, but it is absent.

The solar arrays were not designed to withstand significant loads such as that from perhaps 30 centimeters (1 foot) of carbon dioxide frost, so our interpretation is that this panel has collapsed. It is currently not know how much of the seasonal frost forms as falling dry-ice snow, in contrast to direct condensation of a surface ice which on Earth would be known as a hoar frost. Thus it is known how fluffy or dense this frost might be.

The comparison of these images also reveals why it has proven so difficult to locate the failed 1999 Mars Polar Lander (MPL). HiRISE searched for MPL after several southern winters had passed, so the hardware likely appears similar to the Phoenix hardware in 2010. The bright parachute is completely hidden by dust and the bright specular reflections are gone. The lander appears as an unusually large shadow from what might appear to be a boulder that is undersized relative to the shadow. The backshell has an unusual shape for a boulder, because it came to rest on its side. There is still a dark spot where the heat shield came to rest, but the bounce mark to the west is not apparent. In other words, in 2010 there are only very subtle hints of the Phoenix landing event in HiRISE images.

If that's all we had to go by, if Phoenix had failed and we were searching for it over a large landing ellipse after a polar winter had come and gone, it would be extremely difficult to deduce that this was the landing site or to understand if the landing itself had succeeded.