by neufer » Thu Jun 05, 2014 5:55 pm

Chris Peterson wrote:tomatoherd wrote:neufer wrote:

Galaxies grow bigger with time from absorbing/assimilating more gas and other galaxies.

Galaxies DO NOT grow bigger with time due to the expansion of the universe.

you are correct, I'm guessing: they do not relative to another "inside" observer. But they do absolutely, i presume, to an outside observer, as does everything if space/time is expanding. Of course the only outside observer is God et al.....

No. The expansion of spacetime is not uniform. Gravity easily overpowers expansion. Regions with strong gravitational fields don't expand. That includes galaxies. Spacetime is expanding around them, not through them.

I like to think of normal expansion as analogous to being

kinetically shot out of a cannon.

However...there are possibly other more

dynamic forms of expansion:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_big_rip wrote:

<<The Big Rip is a cosmological hypothesis first published in 2003, about the ultimate fate of the universe, in which the matter of the universe, from stars and galaxies to atoms and subatomic particles, is progressively torn apart by the expansion of the universe at a certain time in the future. According to the hypothesis, the scale factor of the universe and with it all distances in the universe will become infinite at a finite time in the future. It is important to note that the possibility of sudden singularities and crunch or rip singularities at late times occur only for hypothetical matter with implausible physical properties.

The hypothesis relies crucially on the type of dark energy in the universe. The key value is the equation of state parameter w, the ratio between the dark energy pressure and its energy density. At w < −1, the universe will eventually be pulled apart. Such energy is called phantom energy, an extreme form of quintessence.

A universe dominated by phantom energy expands at an ever-increasing rate. However, this implies that the size of the observable universe is continually shrinking; the distance to the edge of the observable universe which is moving away at the speed of light from any point moves ever closer. When the size of the observable universe becomes smaller than any particular structure, no interaction by any of the fundamental forces (gravitational, electromagnetic, weak, or strong) can occur between the most remote parts of the structure. When these interactions become impossible, the structure is "ripped apart". The model implies that after a finite time there will be a final singularity, called the "Big Rip", in which all distances diverge to infinite values.

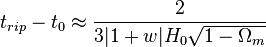

The authors of this hypothesis, led by Robert Caldwell of Dartmouth College, calculate the time from the present to the end of the universe as we know it for this form of energy to be

where w is defined above, H

0 is Hubble's constant and Ω

m is the present value of the density of all the matter in the universe.

In their paper, the authors consider an example with w = −1.5, H

0 = 70 km/s/Mpc and Ω

m = 0.3, in which case the end of the universe is approximately 22 billion years from the present. This is not considered a prediction, but a hypothetical example. The authors note that evidence indicates w to be very close to −1 in our universe, which makes w the dominating term in the equation. The closer that the quantity (1 + w) is to zero, the closer the denominator is to zero and the further the Big Rip is in the future. If w were exactly equal to −1, the Big Rip could not happen, regardless of the values of H

0 or Ω

m.

In their scenario for w = −1.5, the galaxies would first be separated from each other. About 60 million years before the end, gravity would be too weak to hold the Milky Way and other individual galaxies together. Approximately three months before the end, the Solar System (or systems similar to our own at this time, as the fate of the Solar System 7.5 billion years in the future is questionable) would be gravitationally unbound. In the last minutes, stars and planets would be torn apart, and an instant before the end, atoms would be destroyed.

According to the latest cosmological data available, the uncertainties are still too large to discriminate among the three cases w < −1, w = −1, and w > −1.>>

[quote="Chris Peterson"][quote="tomatoherd"][quote="neufer"]

Galaxies grow bigger with time from absorbing/assimilating more gas and other galaxies.

Galaxies [b][u]DO NOT[/u][/b] grow bigger with time due to the expansion of the universe.[/quote]

you are correct, I'm guessing: they do not relative to another "inside" observer. But they do absolutely, i presume, to an outside observer, as does everything if space/time is expanding. Of course the only outside observer is God et al.....[/quote]

No. The expansion of spacetime is not uniform. Gravity easily overpowers expansion. Regions with strong gravitational fields don't expand. That includes galaxies. Spacetime is expanding around them, not through them.[/quote]

I like to think of normal expansion as analogous to being [b][u][color=#0000FF]kinetically[/color][/u][/b] [url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGpS6LHeBC0]shot out of a cannon[/url].

However...there are possibly other more [b][u][color=#FF0000]dynamic[/color][/u][/b] forms of expansion:

[quote=" http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_big_rip"]

[float=right][img3="[b][color=#FF0000][size=135]God et Al: Big Al is the costumed mascot of the University

of Alabama Crimson Tide in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.[/size][/color][/b]"]http://media.al.com/live/photo/big-aljpg-5f07d2f50271595e_large.jpg[/img3][/float]

<<The Big Rip is a cosmological hypothesis first published in 2003, about the ultimate fate of the universe, in which the matter of the universe, from stars and galaxies to atoms and subatomic particles, is progressively torn apart by the expansion of the universe at a certain time in the future. According to the hypothesis, the scale factor of the universe and with it all distances in the universe will become infinite at a finite time in the future. It is important to note that the possibility of sudden singularities and crunch or rip singularities at late times occur only for hypothetical matter with implausible physical properties.

The hypothesis relies crucially on the type of dark energy in the universe. The key value is the equation of state parameter w, the ratio between the dark energy pressure and its energy density. At w < −1, the universe will eventually be pulled apart. Such energy is called phantom energy, an extreme form of quintessence.

A universe dominated by phantom energy expands at an ever-increasing rate. However, this implies that the size of the observable universe is continually shrinking; the distance to the edge of the observable universe which is moving away at the speed of light from any point moves ever closer. When the size of the observable universe becomes smaller than any particular structure, no interaction by any of the fundamental forces (gravitational, electromagnetic, weak, or strong) can occur between the most remote parts of the structure. When these interactions become impossible, the structure is "ripped apart". The model implies that after a finite time there will be a final singularity, called the "Big Rip", in which all distances diverge to infinite values.

The authors of this hypothesis, led by Robert Caldwell of Dartmouth College, calculate the time from the present to the end of the universe as we know it for this form of energy to be

[img]http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/e/7/b/e7b9d8540034e0c11c6a677e348c2875.png[/img]

where w is defined above, H[sub]0[/sub] is Hubble's constant and Ω[sub]m[/sub] is the present value of the density of all the matter in the universe.

In their paper, the authors consider an example with w = −1.5, H[sub]0[/sub] = 70 km/s/Mpc and Ω[sub]m[/sub] = 0.3, in which case the end of the universe is approximately 22 billion years from the present. This is not considered a prediction, but a hypothetical example. The authors note that evidence indicates w to be very close to −1 in our universe, which makes w the dominating term in the equation. The closer that the quantity (1 + w) is to zero, the closer the denominator is to zero and the further the Big Rip is in the future. If w were exactly equal to −1, the Big Rip could not happen, regardless of the values of H[sub]0[/sub] or Ω[sub]m[/sub].

In their scenario for w = −1.5, the galaxies would first be separated from each other. About 60 million years before the end, gravity would be too weak to hold the Milky Way and other individual galaxies together. Approximately three months before the end, the Solar System (or systems similar to our own at this time, as the fate of the Solar System 7.5 billion years in the future is questionable) would be gravitationally unbound. In the last minutes, stars and planets would be torn apart, and an instant before the end, atoms would be destroyed.

According to the latest cosmological data available, the uncertainties are still too large to discriminate among the three cases w < −1, w = −1, and w > −1.>>[/quote]